From the Series of Essays

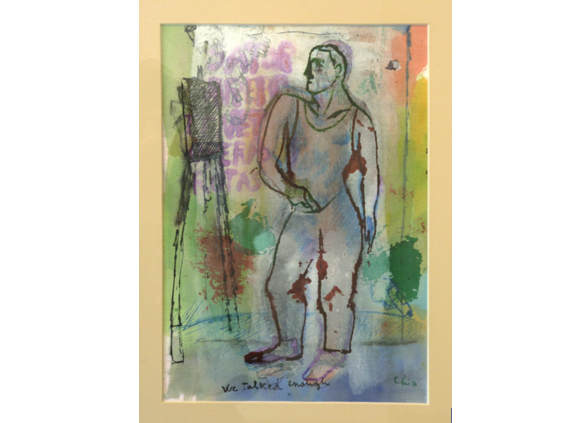

Ritual Practices by Elaine Smollin

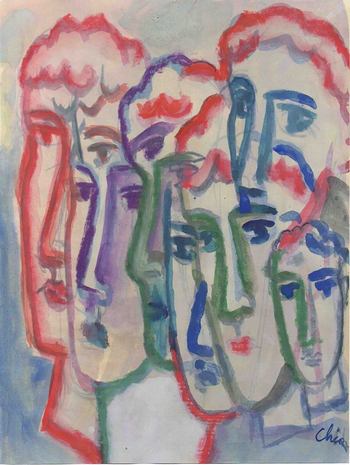

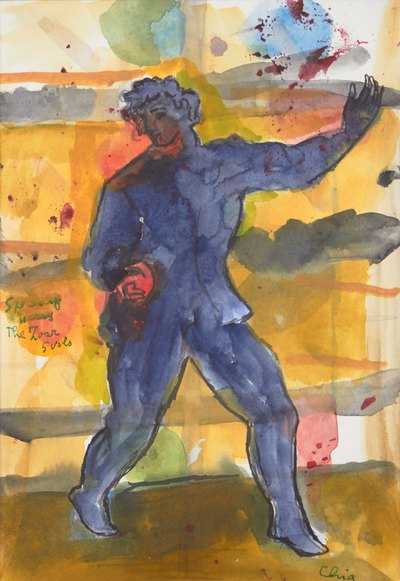

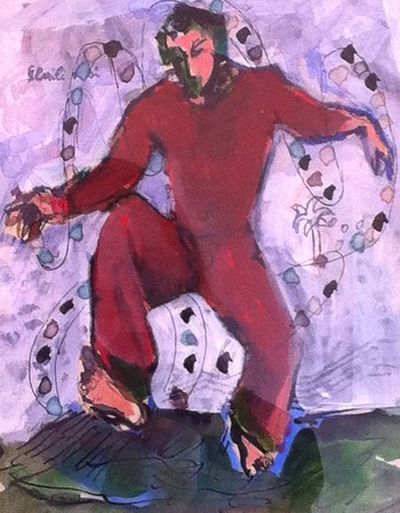

Sandro Chia’s imagery returns to New York with his series Sator Arepo at

Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects through May 25th, 2014.

Eternally itinerant men are a fact of all societies. Images of wanderers, warriors, pilgrims and saints have enlivened walls with the historical record of human behavior since antiquity. Yet, these men are not as solitary as they may seem at first glance.

Who made this imagery? Among the eternal wanders were also the world’s itinerant painters. They formed the bedrock of everyday imagery in the periphery of empires. Their work is the outcome of seismic shifts in world demographics, in which a gifted image-maker may be an apprentice in a capitol city one day and becomes a refugee the next, painting scenes from everyday life somewhere in another world. And so it has been throughout human existence.

Like the icon painters of Constantinople making their way west to Venice, images of the deities and solitary men have always been accompanied by conventions of imagery that exemplifies matters faith. Embodying the behaviors lost to time and successive violent regimes, the solitary man has a long history of carrying with him, artifacts, totems and abstract formulations for being in the world. It’s a part of our universal experience to transform habits of existence from another time and place to form allusions to an indispensible new reality through the wanderers’ example.

This brings up the question of Chia’s bear. Who is the small young bear in these Sator Arepo images? To give him an identity, is a matter of consciousness, often lost to us Moderns. Given the timeless aura of these incisively drawn and colored works, you can easily accept a referential air that can evoke the mysterious ethos of cult practices such as the old Basque and Sardinian practices of the roaming Mamuthone.

These are men adorned with bearskins and regalia that signify spiritual forces of the forest. They express humanities’ ability to communicate on a level of divinity with animals; in short, they bestow good luck.

Does this little Mamuthone speak to the long history of painting, its practitioners and their fluency with mediums- real or imagined? Chia’s figures meld well with those from Hellenism to Blake that reinvent ritual behaviors through a vibrant imagist spirit. The Manuthone is simply a young boy and a young bear. Through his innocence his presence among artists over millennia speaks for much more.

By way of ethnographic analogy, here is an image by a distant compatriot whose identity and imagery would be totally lost but for the work of clever preservationists. An itinerant Italian decorative painter born on the Isle of Elbe in 1752 emigrated (or fled) to the pirates’, privateers’ and revolutionaries’ port town of Newport, Rhode Island some time around 1800. The few surviving fragments of his hand-painted wall papers attest to styles of figuration with a continuous link between the formal portrait, the cartoon, and, a give evidence of a visual culture spontaneously reassembled abroad, which, yes, presents the itinerant man who endures across time and across periods of transitional aesthetic preferences.

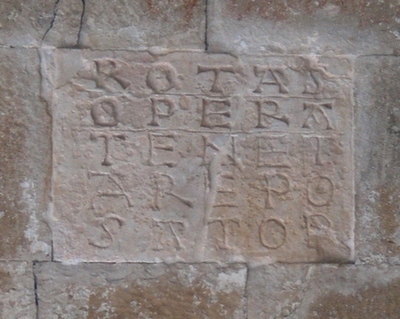

The wanderer is the figure unseen but clearly referred to in ancient hand carved marble Sator Arepo stele like this one of 79 CE found at Pompeii. Among the wordplay arranged geometrically is the term areppo. It derives from ad repo or “I creep towards”. The question of origins of human behaviors that combine our powers of intuition, consciousness and initiative to creep and even run towards our fate abound here.

Interestingly enough, the small young bear in Chia’s works is a companion and a free agent. Unlike the captive, chained, dancing bears still popular in regions from Bulgaria to Sardinia, this tiny chap is a fellow wanderer. He is cognizant of, yet innocent of, the consequences inherent in the imagined purpose of their journey. He is, as yet, a bit unaffected by the consequences of their status as wanderers.

Whose conditions of existence are implied here?

Chia has been acutely aware of the mythical conditions that imbue modern existence while associated with the Transavanguardia movement and as a singular actor in the perpetuation of the painted image. Since the 1960s, European painting and cinema attempted, by necessity, to reconcile post-war new political alliances and even revolutionary aims with aesthetic attitudes, like surrealist and expressionist forms that were abandoned after the war. Roberto Rossellini’s 1947 film, “Germany Year Zero” contributed to a new consciousness embodied by images of the individual.

A wanderer, like Truffaut’s boy (a self recollection) in 500 Blows, establishes a rocky but hopeful future for a wandering boy, unlike the boy-suicide in Rossellini’s film. More recent generations are made aware of our mythological status on the edge of reason by such figures. Chia’s small paintings address our need to formalize the work of our imagination by cultivating images of men with ambiguous origins. Thereby he keeps us wondering what our commonality might be and how we might use it.

Can playful figurative paintings be political? They certainly carry societal histories.

I mentioned Ulysses and Michelangelo in reference to how Chia and the old New Wave cinema call the fabric of society and its evolutionary status into play with Sator Arepo.

Mid-twentieth century Auteur filmmakers shared Transavanguardia’s interest in revealing complex motivations behind new rites of passage involved whenever we exit expired social structures and awaken in a new visual culture. What could explain this aftermath of the cataclysmic days of the twentieth century better than an introspective levity required for a new threshold? This complex puzzle of image creation crossed the line between imagery and narratives that could address fluctuations between vulnerability and courage.

Chia’s simplicity allows this imagery and social histories a chimera-like soul.

The purposeful naiveté in the execution of these works evoke a spontaneity we can trace to the fundamental experience of cinema. Each of these small painted works operates as a continuum, not unlike our participation in the one-frame experience of film that incrementally connects our subliminal awareness to an unfolding eternal narrative. We the author create the needed trajectory of Chia’s figures to a broad folly of becoming that is irresistible to the wanderer.

It was none other than Roberto Rossellini who, in the early 1960s, suggested that Jean- Luc Godard explore the behavior of simple everyday people when the limits of reason suddenly fall. This epic about imagination and European wars focuses on the rise and fall of consciousness, much as paintings do. To address this commonality with cinema and painting, Godard introduces the famous scene, “Order and Method”.

The artist’s ability to capture the solitary human spirit becomes the foundational to the language of conquest. At the outset, the boy soldier, Ulysses, addresses a Rembrandt self portrait to exclaim, “The Soldier Salutes the Artist!” He saunters off to ridicule the local populous and plunder what he can, aware that the solider and the artist share an unbroken ability to shape society. Meanwhile, small bears head for the hills.

Godard set out to craft a polemic of still images, appropriation and visual culture.

Prior to the encounter with Rembrandt, the two young antagonists, Ulysses and Michelangelo, crossed the Rubicon that separates their peaceful, if dull, rural life to enter a world of ceaseless adventure. Equipped with a minimal capacity for empathy, they discover that, with a little effort, they can explore seemingly boundless dimensions of violence and transform the ordinary into the extraordinary. This leads directly to the task of sorting out a stash of picture postcards that depict the origins of the modern world. Their task is to prepare for the capture of significant monuments. Their seizure, first imagined through pictures, can affect the collapse of the modern world.

In the “Scherzade!” frame Michelangelo casts the image of the Queen on to a pile of pinup girls, repositioning her into another era among a liberated populous- eager to enjoy the sensual rights and rituals previously reserved for her alone.

Sandro Chia has always been mindful of how images of people inherited from antiquity to modernism can reveal the strengths and weaknesses of appropriated imagery.

Use of the figure in recent decades has sadly had its undeserved detractors who deny a broadly held societal need for reflection on figures as vessels for the human condition.

Let’s paint them anyway, as Chia’s, or even as Fra Angelico’s solitary men might say, “Go ahead and mock me. Travesty is a part of my protection against ignorance. The picture plane is a threshold between me and behaviors inside the Rubicon.”

______________

* An informal video on the opening of the Sator Arepo exhibition of Sandro Chia’s work on paper, by the Brooklyn-based artist and writer James Kalm. It includes an interview with the artist Sandro Chia, and the gallery director Steven Harvey. http://inveroart.com/sandro-chia-sator-arepo-at-steven-harvey-fine-art-projects/