What am I doing here?

There is a place in the womb of Bogota, capital of Colombia, where night clubs open at all hours, where prostitutes and transvestites cross their paths, they turn around and collide into each other as if they were atoms on some psychedelic high heels.

There, on the 23rd Street down the Caracas Avenue, an intense noon sunlight paints in yellow a scene already soaked in many colors. Yet not everyone here is touched by the sunlight, some of them lurk like shadows on dirty walls, living with the heavy burden of their vices.

The rest of the neighborhood is a sharp contrast: shops, bakeries and grocery stores conduct their lives business as usual like an oasis in the midst of unhinged lives. I am cruising these streets to meet Linda Ponguta, an artist, who will show me her studio, and as my car pulls to an old red brick building around the block’s corner, I see her waiting for me at the door.

As I climb up a spiral of seemingly endless stairs groping in the dark, trying to catch up with her, I am beginning to understand what she means by saying that there are places to “show”, and

places to “hide”. It’s clear that the fourth floor of this once majestic and now pretty run-down edifice is her place to hide.

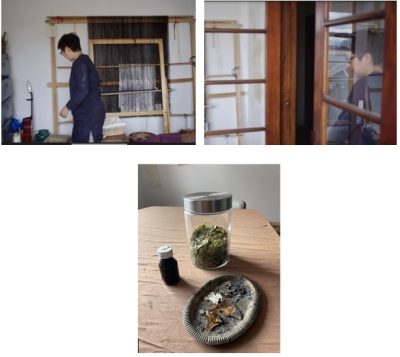

Her hideout or rather “her refuge” is a mixture of what is remained on the beach following the onset of a low tide: tons of drawings glued to the walls, bamboo rods piled up in a corner, a guitar, a loom, a lock of tree branches, a heap of tobacco leaves and a table in the middle of the room that seems to float in the air… The room smells of wood, mountain and salt.

There is a glass cylinder on a beige canvas used as tablecloth; it looks like a small fish bowl and it is filled with coca leaves, next to a dark brown plastic jar. Linda pokes her index finger into the jar for a dark resin of tobacco to be spread on her gums before chewing coca leaves, as if she were placing a wreath around her mouth before a long procession of words begins to come forth. Linda is now ready to talk.

“Art is like this,” she spreads out her arms pointing to me her studio,” an ‘improvised’ space where I can light up a candle to see the reality around me, to know what is happening in this world in terms of a mental construct by all of us.”

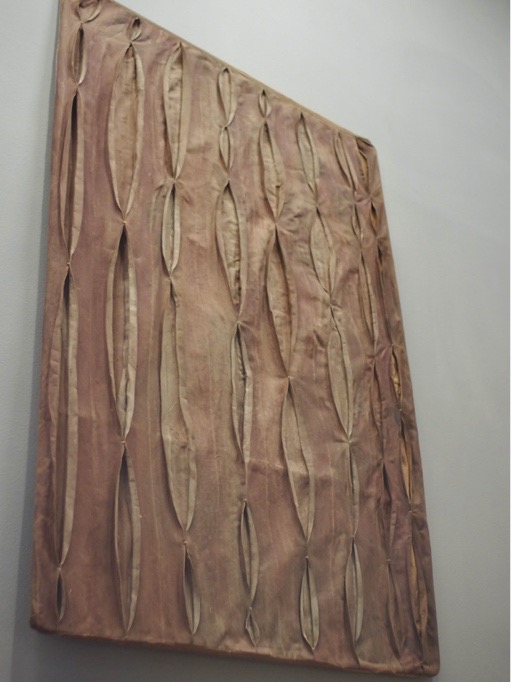

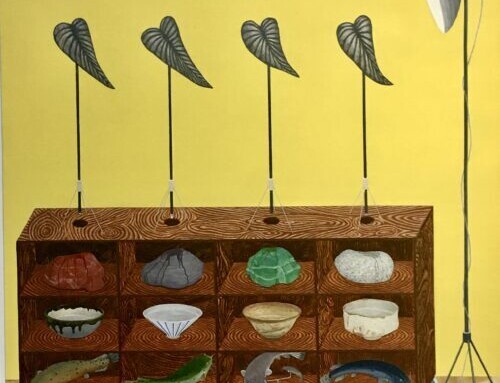

Her recent works, “Lodazal”, “Garganta”, and “Tasqua” , currently shown at the Espacio Continuo gallery were all conceived in the confines of these walls furnished with huge dirty windows pecked by sick pigeons.

“I need to work in spaces where a lot of pain dwells”, she points out, “there is a different Linda breathing in a different place. Here I see myself as a warrior trying to enter and feel the human condition under a systemic machinery of pain, prostitution, crimes and death.”

The first time that she experienced this took place at an abandoned labyrinthic 14-floor telecommunications building called “Florentino Vesga” in the west central section of the city, where she had lived for six years, 2012 to 2018.

Whatever she got out of that space helped her finish her university thesis called “Fragmentos para mañana” (Fragments for Tomorrow), a series of art projects using objects and materials found inside the building and its surroundings, including a video showing indigenous people felling a Maguaré tree to build a drum; an installation of a tree that was severed, making half of it in wood and half in cement; an installation utilizing several light tubes that she had found abandoned in the building, and a sculpture recycling the building’s existing office divisions. Some of these works were later shown separately in different exhibition spaces and locations, including the prestigious National Art Salon and the very abandoned building that she had lived.

Another work of the series is “Transmisión”(Transmission), which consists of rotten fruits placed on a cement plaque, acquired in 2020 for collection of Colombia’s central bank, Banco de la República.

Having completed her series about the city, the artist embarks on a journey to the jungles bordering Colombia with Ecuador seeking the teachings of the indigenous shaman Isidro. In the midst of nature, medicinal plants and sacred ancestral places she was shocked to find an abandoned extensive oil pipeline, thus she found her ancestral calling and created “Árbol palo” (Tree Post) and “Redes vacías” (Empty Nets), both works inspired by ancestral concepts of life and death.

Having closed another cycle of her work, the artist intuitively begins a new one in a new site to satisfy a new curiosity. This time her destination is the coffee plantations on the steep hills of Tambillo, Huila, southwest of Colombia, to experience the life of a coffee farmer and then went all the way to Riviera, to pick cocoa beans.

“In those landscapes”, she shows me her hands, “I realized that I am a sculptor because I like the tough work of making things and carry heavy loads”.

In 2019, Linda was invited by the international cultural association of Hawapi to be part of a group of artists for an itinerary “encuentro” event far away from the art circles in the city. She lived in the property of a subsistence farmer and environmental activist, Máxima Acuña, in the Andean Cajamarca State of Peru, who has since 2011 resisted attempts by a gold mining company to evict her from her own property and fought to preserve the “Blue Lagoon” area. In an effort to protect and surveil the land, the artist literally developed a large-scale project called “Ojos de la tierra” (Land’s Eyes) walling in Maxima’s house, which was made in stones and earth, utilizing materials from mother nature. Linda’s hands work with the hands of nature.

Then, Linda is forced into the Covid 19 pandemic lockdown for one year, trapped in her apartment in Bogota, hatching baskets and plans for new travels. During the quarantine, she worked online with Marcela Teteye of the native Bora and Okaina communities of La Chorrera in the Amazons and made several works, one of them, “Recogedor “(Dustpan) was auctioned in 2022.

“The vine used to weave the baskets”, says the artist excited, “grows in the lower parts of the jungle, where the Conga ants go to die, it grows out of the decomposition of the bodies of the ants, it’s magical.” She learned this from long conversations and story-telling from her studio mate, Isaías Román, a sculptor with lots of knowledge about the Amazon Huitoto tribe traditions.

In November, she plans to join the Kogui indigenous community in Sierra Nevada Mountain range in Santa Marta, along the Caribbean coasts of Colombia. She wants to learn from Catalina Gil Dingula how to spin and knit the “mochila”, a typical hand-made rucksack used by the indigenous. She wants to understand the meaning of knitting as a spiritual healing process and its connections with the region.

She does not stop there, her spirit goes for more until 2024, before she plans to set out to a new destination, this time, to the largest open-pit coal mine field in Latin America, the Cerrejon, in the northern Colombian Guajira province, going for a single goal: “to experience a place where to be human could be a devastating impact.”

A long silence has brought us back to her “hidden space” in the sickly heart of the neighborhood, backed by the Maria Reina chapel. Her cat scratches the door of her room, wanting to get out…I also want to get out, there is something in the air that hurts the silence and mortifies our conversation. Here one can breathe in pain, but she wants this, as a way to awaken into inspiratio

I ask her how long she plans to stay here. She smiles and tells me that she will stay in this place until the end of 2023 when she finishes her Fine and Visual Arts Master’s Degree thesis at the National University that is based on “my being in this place”.

I try to hide my urge to leave before the sun sets and the night paints in black this sad and delirious neighborhood.

We walk to where my ride awaits, her childlike demeanor is in sharp contrast against the twisted air of the neighborhood. At 32 she still seems to be that excited 13-year-old that made her first art creation at her grandmother’s place: she built a small house with plantain leaves so that she could lock herself in it, light up a candle and listen to the sounds of the open field.

Since then, the artist has never stopped turning her thoughts and ideas into works of art, installations, sculptures, “hidden spaces”, whatever you want to call them, with the residues of this world.