From the Series of Essays

Ritual Practices by Elaine Smollin

Soutine knew it.

The materialization of feeling can preserve a fleeting world.

While he cultivated this affect, Soutine found sanctuary in a series of cities and towns, ultimately fleeing even Paris. While intensifying chaos institutionalized Diaspora as a way of life, for him, Expressionism became a means of continuity.

Expressionism for Soutine, as it was for Chagall, was a painterly stand against a societal shift toward the alignment of art and design within Bolshevik ideology. Soutine lived out the war in Paris while Chagall and his wife were immersed in the vibrant cultural scene in Vitebsk, home to Mikhail Bakhtin, from 1920-1924. Chagall was head of the Vitebsk art school until replaced by Malevich after the war. A Soviet critic said of Chagall in 1925,

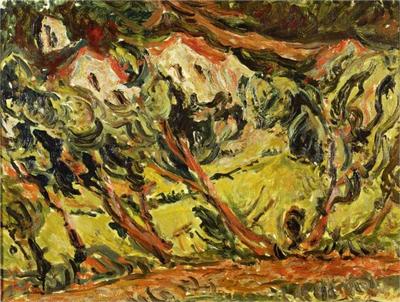

..the petit-bourgeois believed himself naturally to be in hell and found no place among the Bolsheviks, despite his ultra-revolutionary words and acts. And he went away, far, very far, with one sole hope: to succeed in Paris. For Soutine in Vilnius, international trends from Expressionism to Symbolism and Constructivism had traction. He departed from art school in Minsk for Vilnius Art Academy in 1913. At the foundations of the art school building, from its origins near his native Belarus, a mysterious urban stream, the Vilnėle, flows by. It is legendary to locals. Meandering as if designed for Expressionists, its very name means, “to surge”. Soutine’s art school was located in Uzupis across the river (Uz to cross, Upis river) from stunning Baroque cathedrals, including Saint Bernadine and the diminutive Saint Anne’s Gothic chapel, a favorite of Napoleon on his advance to Moscow. Another sacred structure impressed Napoleon, the Great Synagogue of Vilna, home to the Vilna Gaon. Everywhere Soutine may have turned, the twisting lanes led on to every conceivable faith, and flowed west. Like the beguiling urban creek of his youth, “the Surge”, the very tactile painterly drawing of Expressionism may look turbulent, but for the works in this exhibition, surface tempest is an illusion. The painterly tension implied as impasto in reproductions, was made with a gentle elegance of touch, so thin, that in, “Two Pheasants” 1926, the painterly analogy aims at a transparency of surface and a luminosity of flesh. While later Expressionists heap on an implosion of meditative paint, as Leon Kossoff does, as is sometimes inferred, this is not coming from Soutine. As much as Kossoff’s forest may seem to sway to the same turbulence, the paintings at Kasmin Gallery show that the two Expressionists place different demands on the paint. To Kossoff, whose familial lineage springs from a similar region to Soutine’s, the excavation of heritage is literally in the paint as defined by his contemporary Frank Auerbach. Soutine, “Landscape at Ceret, with Red Trees”, c. 1919 Now there’s the question of the tablecloths, carnality, and the special significance of the handling of textiles. Among east Europeans and certainly among others-in-Diaspora who Soutine embraced, these are timeless artifacts of a world with no disposable income and no throwaway culture. Like the sophistication of nomadic Celtic and Scythian artifacts of centuries past, handmade tablecloths are emblematic of love, safety and care for the traveller and his meal. They are as plain as a scrap of linen or trace centuries’ of pattern sewn through the crafting of instinctive rhythms, inborn to the culture. These cloths beneath Soutine’s edible finds were often the handwork of the blind, whose intuitive handwork he would have known. To an eye from the Pale of Settlement, these cloths represented home in all its manifestations of the era from exile to prison. If the carnal quality of culinary arts distract from the images here, imagine what it was to dine with friends who savored every joint and sinew, tendon and eyeball as treasured fare? These images thrive on the visceral reality of love for the intimate rewards of being simply human. That intimacy comes about through a certain degree of carnage, the effort required to cultivate the palette, the eye, and friends. Modernism was born out of the swinging hinge between the primitive and the industrial worlds. In these conditions, from 1913 – 1943, no one needed to possess an African mask by way of French or Belgian colonization to know the immediacy of the spiritualized façade. Emmanuel Levinas, addressed this in Totality and Infinity: Essay on Exteriority[1], to explore the structure of ethics at its source, within face to face encounters with the Other. Begun as notes as a prisoner of war in Germany and first published in Paris in 1963, it traces relationships between a limited material existence and the spiritual world, located at the intersection of non-verbal experience that lays open between us, as people. Levinas, a principle philosopher of post-war France was born in Kaunas, Lithuania in 1906. His close friend Derrida included writing as a liminal bridge into encounter with the Other. Often Soutine and other modernists abandon light for the weight of color. However, in the 1919 portrait of the young baker, the vibrancy of a young complexion and the floury exterior planes of his face would play well with Levinas’ search for the source of empathy in our face to face encounters described in his work Rappore Face à Face[2]. While Supremacists were departing Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Kiev for Paris; in 1911 and 1913 respectively, Chagall arrives in Paris and Soutine in Vilnius. As widely noted, Soutine’s exposure to Cubism and Suprematism was board in both cities but scarcely tempted him. If there had been any notion of returning east after World War One, to recover the momentum of Expressionist form alive in theater, photography, and, painting that now connected Vilnius to Warsaw and Warsaw to Krakow to Munich, the idea ended with continuous territorial battles that engulfed the region. For Soutine and Chagall, and all the artists of Montparnasse, the Polish Soviet War, 1919 to 1921, had a major impact on cultural life in Paris. Lenin’s aim was to annex Poland, move on into Germany and fast-forward the Third Communist International (1919-1943) world wide. To Jewish émigré or refuge painters, the sight of Lenin in Paris (1909-1911) or that of the great orthodox political theologian, Sergius Bulgakov (1923-1944) was as usual as that of Man Ray or Buñuel. Which leads us to the forks on the hare. This embrace of hung game by two animate forks, (at the time, before being skinned, game animals such as hare were first air-dried and aged), can be likened to the repetitious partitioning of east Europeans from their cultures. The dominant colonizing powers could choose to expel people together with their faith and language, or to enforce internal exile, during which time, one might stay within any province of an empire or the Pale of Settlement but with prohibition of one’s language. This still life with hare may show an embrace by disembodied hands for the sake of noting the unseen force behind prohibitions that over time become self-induced censorship. This psychic condition was so familiar and lingered on to become so commonplace during the Soviet period, that to see its analogy in the unskinned hare with forks is emblematic of that psychic seizure and the relentless attempts of ideology to penetrate the body social. As if to liberate the flesh from this dilemma, let’s consider the substance of Expressionist paint handling by Cecily Brown whose father, David Sylvester, helped to form Soutine’s reputation for the remainder of the twentieth century. ______________ *Cover image: Chaim Soutine – Landscape 1918, Oil on canvas.

Oil on canvas, 21 ¼ x 25 1/5”, Private Collection