by Light-man

In New York City, there is one day a week that you do not have to pay to go to the museum. On that day, the Museum of Modern Art gets so crowded that you feel that you have made a mistake and walked into the Grand Central Station.

I went to see the museum’s current exhibition Gauguin: Metamorphoses on a normal day, when an adult ticket costs US$25, and was surprised to find it as packed as any free day. I thought that it was because there were other important shows at the museum, such as a retrospective of the German artist Sigmar Polke (1963-2010) called Alibis or the recent body of work of the iconic American artist Jasper Johns called Regrets.

Besides, as a member of the cloakroom had confided in me, New Yorkers always filled up the museum on rainy days. Yet, in spite of the rain and the Alibis or Regrets, I found that the crowd at the Metamorphoses exhibition to be much larger, more ethnically diversified, and more focused on each of Gauguin’s work.

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Two Marquesans, c. 1902

Oil transfer drawing

Sheet: 12 5/8 x 20 1/16″ (32.1 x 51 cm)

The moment I stepped into the sixth floor, I understood why. This was one of those exhibitions that they rarely showed to the public, one that allowed the viewer to be surprised and discover something they had not seen before.

When we hear the name Gauguin, we tend to associate him with colors. But this show has nothing to do with his use of colors.

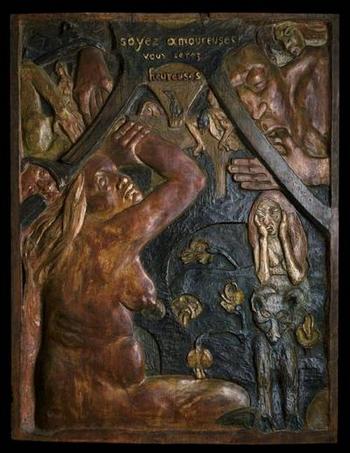

Right at the entrance, I saw a series of woodcut prints of the Volpini Suite, Gauguin’s first attempt at printmaking, followed by the Vollard Suite series of woodcut images with suggestive titles such as “Be In Love and You Will Be Happy”.

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Be in Love and You Will Be Happy, 1889

Painted lime wood

37 3/8 x 28 3/8 x 2 1/2″ (95 x 72 x 6.4 cm)

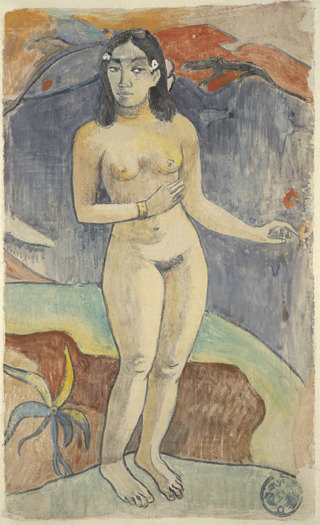

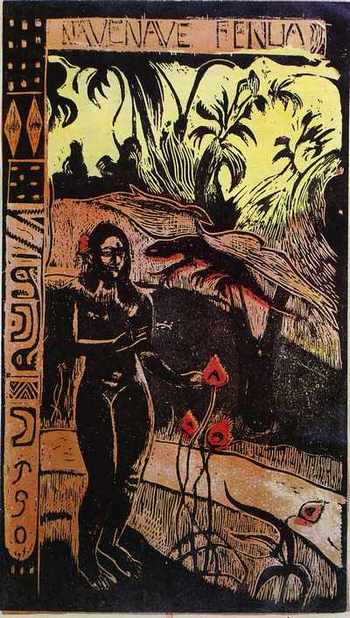

I was particularly taken by the prints called Nave Nave Fenua (Delightful Land), of the Noa Noa (Flagrant Scent 1893-1894) series, the repetitive interpretations of one single composition of a naked woman in the midst of a place that I supposed was paradise with wild trees and flowers and a huge lizard on a path behind her, flanked by a stripe of what appeared to be native symbols.

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Nave nave fenua (Delightful Land), state IV/IV, from the suite Noa Noa (Fragrant Scent), 1893–1894

Woodcut with hand additions

Composition: 13 15/16 × 8 1/16″ (35.4 × 20.4 cm)

Sheet: 15 1/2 × 10″ (39.3 × 25.4 cm

There were more than 150 rarely seen art works, comprising mostly of the artist’s prints, his pioneering oil transfer drawings, delicate watercolor monotypes, work on paper, wood reliefs and sculptures, accompanied by a few carefully selected paintings related to a specific period of time before his death in 1903.

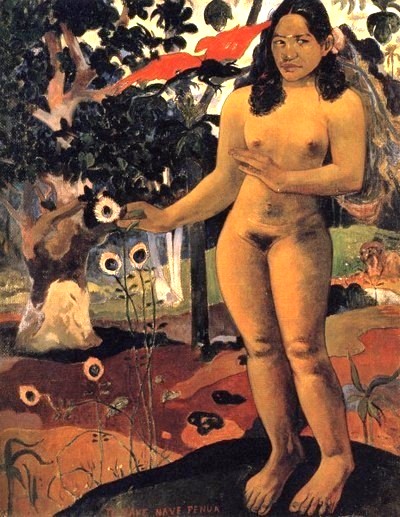

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Te nave nave fenua (The Delightful Land), 1892

Oil on canvas

36 1/4 × 28 15/16″ (92 × 73.5 cm)

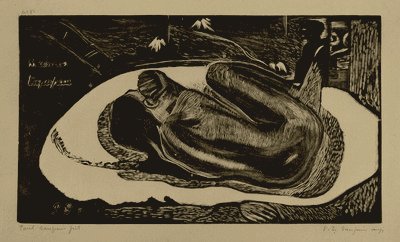

Unlike his best known post-impressionist paintings, Gauguin’s prints showed dark and diffused imageries of untold tales and spiritual ventures to the unknown, just as suggested by some of the titles like Te Atua (The Gods), Te Faruru (Here We Make Love), Te Po (Eternal Night),Oviri (Savage), Tahitian Idol, and Manau Tupapau (Watched by the Spirit of the Dead).

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Manao tupapau (Watched by the Spirit of the Dead), state I/IV, from the suite Noa Noa (Fragrant Scent), 1893–1894

Woodcut

Composition: 8 1/16 × 14″ (20.4 × 35.5 cm)

Sheet: 8 1/8 x 14 1/8″ (20.7 x 35.8 cm)

For me, to physically see these works by Gauguin is a rewarding experience. It offers an opportunity to the viewers to appreciate Gauguin’s creative process, and be inspired, since we can clearly witness how one of the greatest artists in history explored the limitless possibilities of art in terms of technique, concept and selection of places, themes, and objects that had inspired him.

In his creative process, I noticed that he had a tendency of finding imageries by repeating the process with a variety of technical approaches, allowing them to evolve and metamorphose into the unexpected through time.

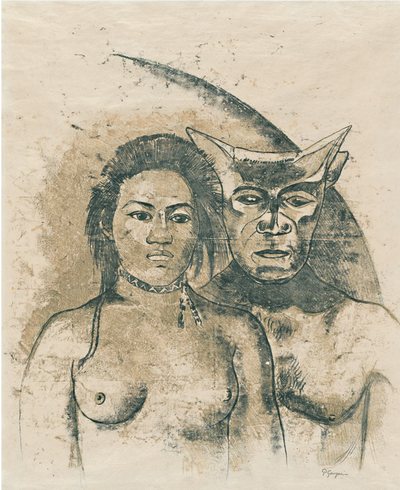

It is not known to many people that he had actually invented a cutting-edge multi-medium technique in 1890 during his years in Tahiti to transfer images that combined drawing with painting and printmaking. He kept accidental markings and made them part of the art work; and boldly settled with a monochromatic, subtle, somber approach to his imagery. These transferred images are mysterious, dark and strangely luminous at the same time, and they reminded me of some Eastern religious drawings as they seemed to poke the prelude to the world beyond.

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Tahitian Woman with Evil Spirit, c. 1900

Recto: oil transfer drawing; verso: graphite and colored pencil

Sheet: 25 9/16 × 18 1/8″ (65 × 46 cm)

The technique is best described in Gauguin’s own words in a 1902 letter to his patron Gustave Fayet: “First you roll out printer’s ink on a sheet of paper of any sort; then lay a second sheet on top of it and draw whatever pleases you. The harder and thinner your pencil (as well as your paper), the finer will be the resulting line.”

The pressure of the pencil caused the ink from the bottom sheet to transfer to the back of the top sheet. After the sheets were peeled apart, the transferred image became the final art work.

These drawings show Gauguin’s consistent obsessions of icons of non-Western cultures. In one of his oil transfer drawings, the Tahitian Woman with Evil Spirit, Gauguin used the photo of a young girl from an island in Polynesia to draw the main naked female figure, and for the horned half-man half-beast character appearing behind her, he used one of his own sculptures as model. The sculpture “Head with Horns” is also on view.

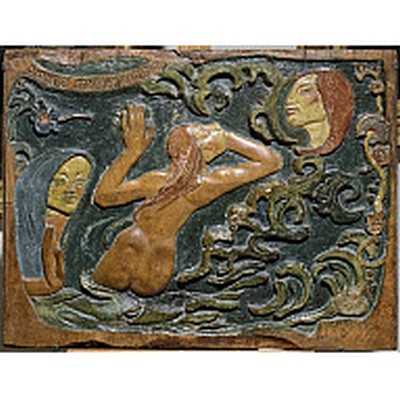

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Be Mysterious, 1890

Painted lime wood

28 3/4 x 37 3/8 x 1 15/16″ (73 x 95 x 5 cm)

The show also displays a series of Gauguin’s painted wood reliefs and sculptures, including one of his own favorites, the “Oviri” (Savage), that clearly addresses issues of primitivism and savagery.

Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Oviri (Savage), 1894

Partly enameled stoneware

29 1/2 x 7 1/2 x 10 5/8″ (75 x 19 x 27 cm)

It is obvious that Gauguin was interested in cultures untainted by the European civilization such as Tahiti, but his approach was anything but simplistic. Looking at this collection of work that reflects his creative process, I felt that he was trying to find a soulful place where the delicate, extremely refined aesthetic values of European art at the moment and the apparently direct, uncouth and honest expressions of the primitives were merged and metamorphosed into one.

And when I walked out of the museum into the rain with my heart still imbued in the intense yellow light in his oil painting in 1898, the Faa Iheihe (Tahitian Pastoral), I felt with satisfaction that Gauguin had indeed found such a place.

* Image on slider: Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Faa iheihe (Tahitian Pastoral), 1898

Oil on canvas

21 1/4 x 66 3/4″ (54 x 169.5 cm)

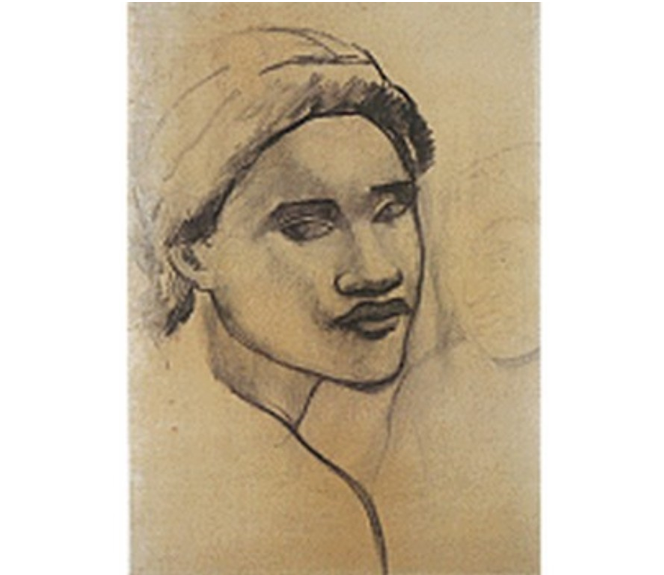

Image on cover: Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903

Study of Two Tahitians, c. 1899

Black pencil and charcoal on paper

Sheet: 16 15/16 x 12″ (43 x 30.5 cm)