“History Keeps Me Awake at Night”, David Wojnarowicz’s large and impressive retrospective exhibition evokes strong feelings of injustice, rage and beauty. It also brings sadness, for it reminds us of a desperate time in American history when AIDS took the lives of friends, lovers, strangers.

Wojnarowicz lived a short life. He had a difficult childhood in New Jersey that included physical abuse and sex work. He was a poet before becoming a visual artist. He had no formal training in art and became known in the East Village art scene of the 80s for creating controversial installations and paintings. Sex and violence played a big role in his art, especially same-sex desire, homophobia, the AIDS crisis and the government’s refusal to address it. Love and loss and spirituality troubled him. The concept of what is the right and wrong conduct preoccupied him until he died of AIDS-related complications at the age of 37.

“To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications”, Wojnarowicz wrote. His art is varied and strong, provocative, violent, incendiary. He always had anger in him and fortunately, he directed that anger into making art. The result was something he did not expect: comfort, for he realized that anger can find comfort when it was made public.

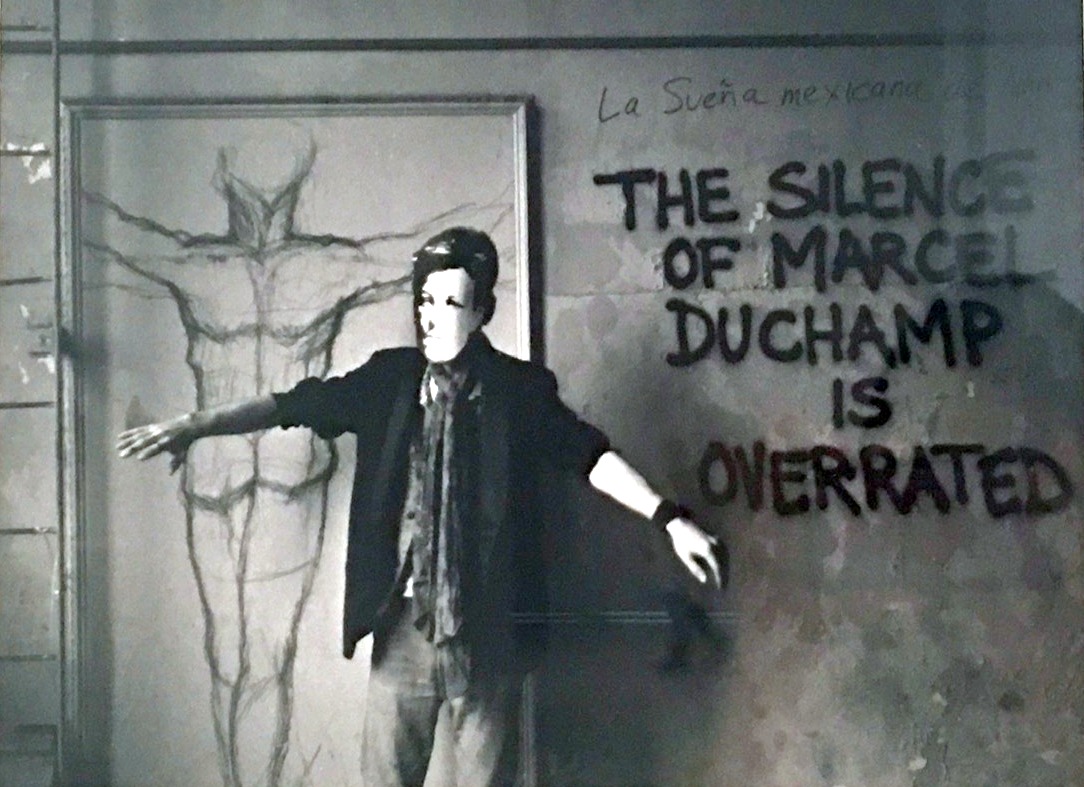

His body of work included photography, painting, print, music, film, sculpture, writing and activism, mixing innovative techniques and styles, always exploring, never settling for one style. The retrospective begins in the late 70s, with a series of photographs he took of himself and friends wearing a mask of his personal heroes such as the French poet Arthur Rimbaud and Jean Genet, the French novelist, poet, and political activist. For “Untitled (Genet after Brassai)”, he turned the iconoclast writer into a saint while in the background, a Christ figure seems to be using a syringe. When criticized, he said that drug addiction was a modern struggle and an emphatic Christ would know how to forgive.

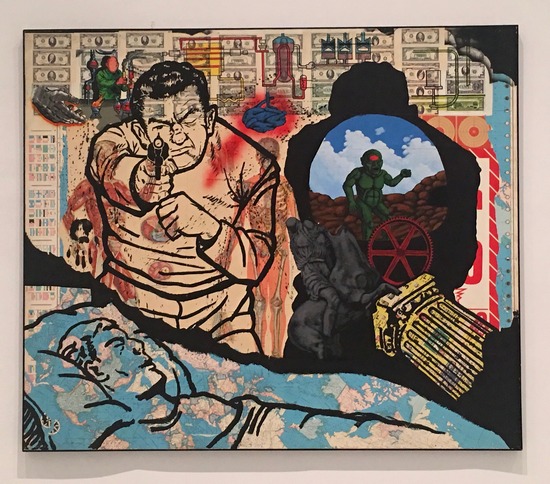

Wojnarowicz’s work is really about America, a place he had described in a 1991 essay as a “tribal nation of zombies…slowly dying beyond our grasp”. In the painting titled “History Keeps Me Awake at Night”, he portrayed a dystopic vision of American society fraught with chaos and violence, disturbing the sleep of a man below

“Mexican Crucifix” was one of the five paintings he created from photographs and film footage taken during a trip to Mexico in 1986. It addressed the forced imposition of Christianity on indigenous Aztec culture. It consists of five panels and one of them depicted Chris on a cross swarmed by ants, a symbol that he used repeatedly in his work. Long after his death, the ant series got him into trouble when the National Portrait Gallery in London was forced to remove photos of the ants due to complains from religious and right-wing groups.

“Wind” was the most personal of his Four Elements series. In it, a red line connects an open window, a baby (his brother’s newborn) and a headless paratrooper on the upper right hand. Wojnarowicz, in his only painted self-portrait, stands next to the paratrooper.

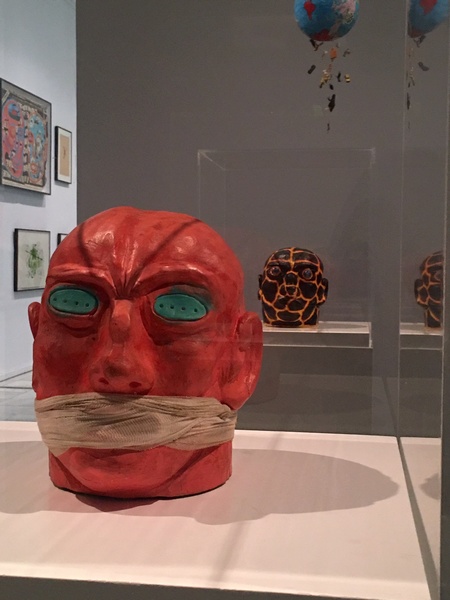

The cast-plaster heads belong to a series of 23 sculptures that represent the number of chromosome pairs in human DNA and the “evolution of consciousness”. Wojnarowicz often used allegory to critique the corrupt society, as if urging the viewer to consider how power should be exercised.

In the four large-scale paintings of exotic flowers, Wojnarowicz intended to show the beauty of the body and its fragility. The flowers represented an allusion to the AIDS crisis, his own illness and the feeling of loss. “Don’t ever give up beauty”, he had said. “We are fighting so that we can have things like this, so that we can have beauty again.”

A quarter-century after his death, the full-scale retrospective acknowledges David Wojnarowicz as not just another “gay artist” but a respected contemporary artist. First exhibited at the Whiney Museum of Art in New York, “History Keeps me Awake at Night” then moved to the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid during summer of 2019, and is now at the Contemporary Art Museum of Luxembourg until February 2020.

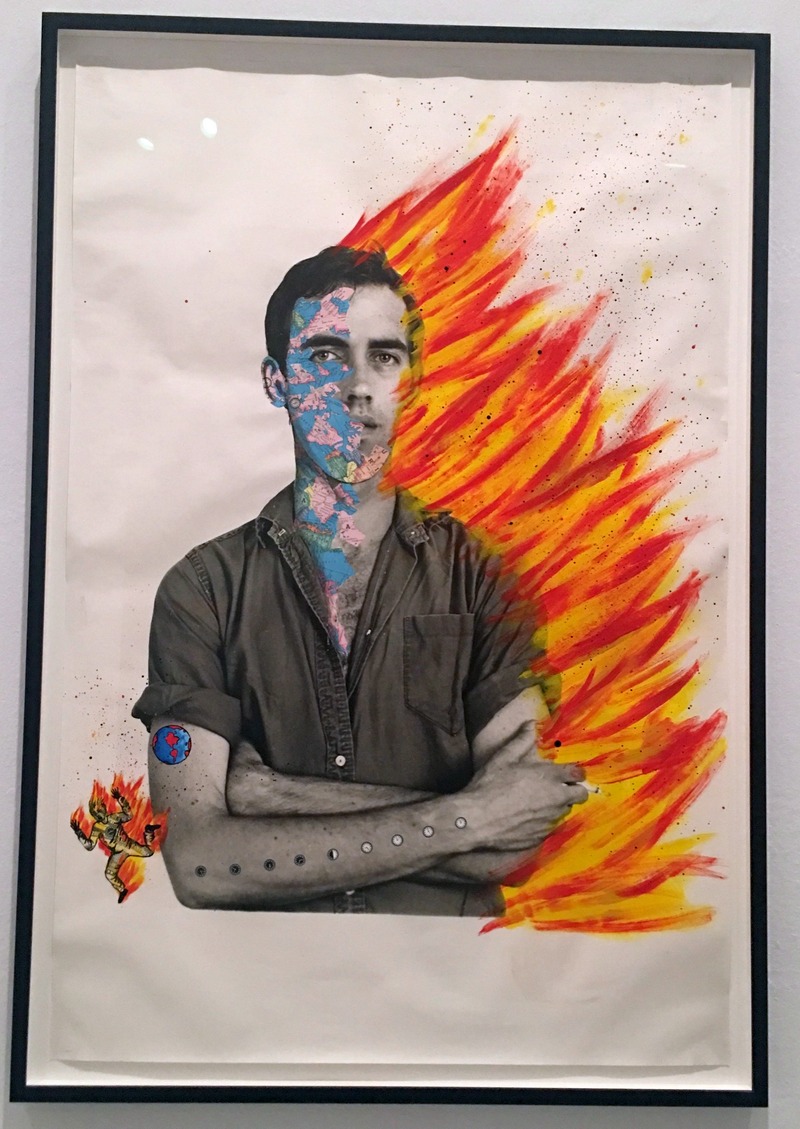

*Image on slider:

Self-portrait, 1959, acrylic and collage on photograph

Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-1979, photogr