by Christina Chow

The other day a nice college art student approached me at a gym in Miami. He heard I was a professional artist so he shared with me his passion to draw on a computer. As a member of the X generation, he did not feel confident to draw with his hands. “I wish I could learn how to draw”, he said.

I wish I had the time to tell him that drawing was not just about learning a new technique or use fancy tools. Other things are also involved: content, proportion, harmony, spirit, hard work… Then, I suddenly realized that in this highly competitive and pragmatic digital age, art crafted from the lengthy process of manual labor is no longer widely practiced as in the past. It has become a rare commodity and we have begun to seek out the long lost value of art by unearthing the past, by honoring our memory, by remembering, and then somehow finding it strangely new.

Museum exhibitions of old masters are getting more attention; the nostalgia for the Picasso’s, the Da Vinci’s, the Fra Angelico’s… ancient sculptures, tiles and murals, even caves filled with mysterious symbols, movies referencing dusty mummies and dinosaurs, DNA testing to find our roots and ancestry…appears to have gained upswing momentum.

As I reflect on the contemporary tendency to search for the past, I miraculously stumbled on one powerful art event taking place right now, a particularly moving artwork of a teacher, an old friend.

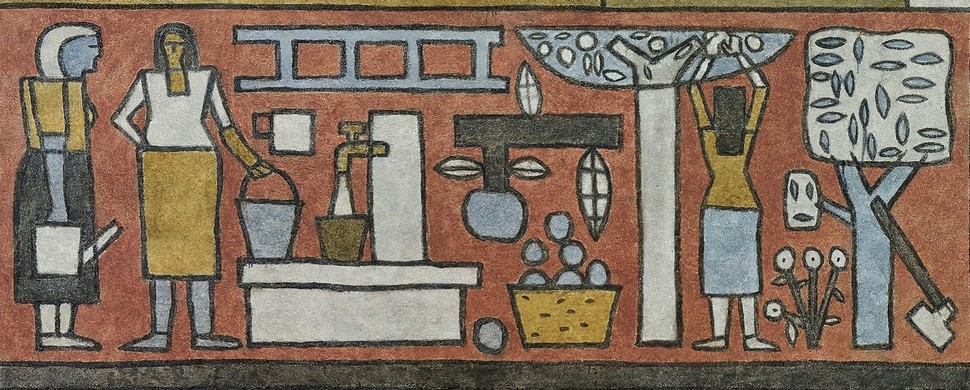

It is a mural, not overly huge in scale, 8 meters x 3 meters (26.24 x 9.42 feet), located in a school in a small country in the remote southern end of the world.

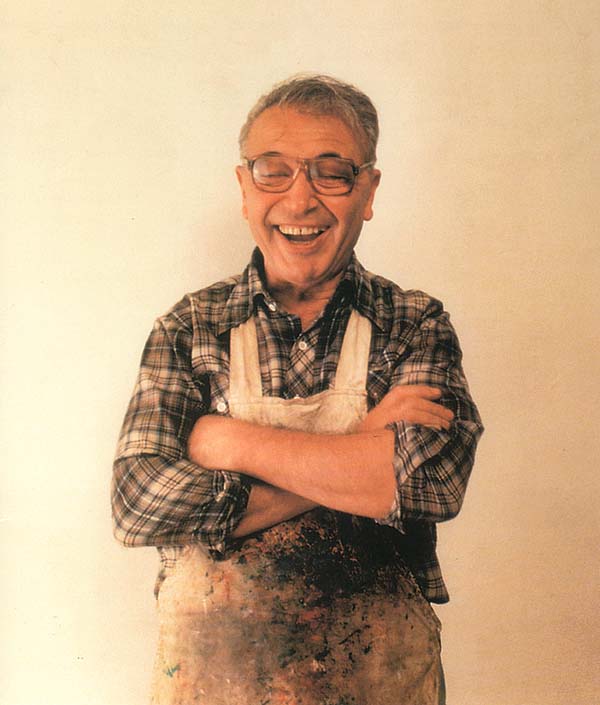

Painted some 60 years ago, the mural was called “Oficio”, which in Spanish means work or labor, and it is a tribute to a variety of works done by people from all walks of life at the time. The painter was the Uruguayan Julio Alpuy who rose to international fame over half a century ago in New York, an artist who worked with different mediums and liked to call himself “laborer of art”. In 1935 he joined in the formation of the Universal Constructivist Movement, one of the most important art events that changed the course of history of South American art.

Alpuy was born in 1919 in the rural areas where manual work with Nature was sacred. That tendency never left him even as he travelled all over the world and in 1961 moved to the Big Apple, where he lived and died of pneumonia in one chilly winter in 2009 at the age of 90.

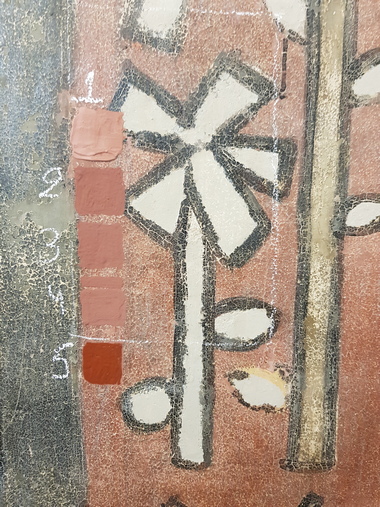

This year Uruguay celebrates Alpuy’s 100thbirthday and one of the first things the Uruguayans did was to commission a large multi-tasking international team of restorers, led by the experienced Claudia Frigerio, to bring the much-damaged mural back to life.

Sounds an easy job in any country equipped with an existing infrastructure for restoration, but Uruguay is a newcomer in the preservation of its cultural heritage and the Alpuy mural restoration signals just the beginning.

Located in the corridors of the Liceo Damaso Larrañaga school, half the mural suffered serious chromatic and material loss caused by environmental inclemency such as sunlight and humidity. The challenge was huge; the aggravating chromatic loss was particularly difficult due to the sophisticated tonal sensitivity the artist had mastered. It required resources, research, and above all, an unflinching decision to bring back a message of spirit of constructive art.

For 12 grueling months, the project accounted for the courageous, hands-on efforts of Uruguay’s Ministry of Culture, the Commission for Cultural Heritage, dozens of artists, former students of Alpuy and members of the Universal Constructivist Movement, a sizable team of restorers involving foreign experts from Mexico and Spain, different institutions and foundations, architects, even school teachers and their young students. It was a mural dedicated to labor, and it inspired a united front of labor for the reconstruction of art. “The whole site became a huge workshop”, said the Commission’s director Rafael Lorente.

Restoration is now finished and the mural is open to public as part of a series of nation-wide activities to honor the artist. It includes a major retrospective exhibition of his extensive trajectory at the National Museum of Visual Arts in Montevideo this December and two more important exhibitions of his work and that of his friends and students at the Mazzoni Museum and the Museum of History of Art (MuHAR).

The fact that the homage to Julio Alpuy began with the restoration of one of his murals in a school is significant. As prolific as his artistic production, so was his role as an educator. He taught wherever he went, and his students were of different ages, races and cultural backgrounds. Braced with an indefatigable spirit, Alpuy taught with passion and left to the new generation a legacy of an art founded solidly in honesty, humanity, and universal awareness.

I remember when I used to visit Alpuy in the 90s in New York. His home/workshop was located in the now hip Noho in Manhattan, inside a co-op building that he and a group of his artist friends built, including the painter Robert De Niro Sr, father of the Oscar winning actor. Each one of them owned one complete floor, each had a specific design. On his floor, Alpuy made two separate areas, the living area and the studio, each with its own entrance.

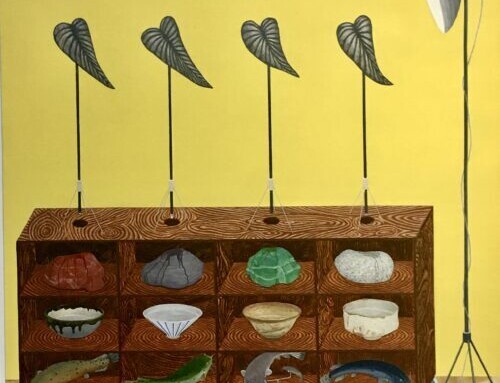

We used to drink tea with biscuits and sat in a sofa surrounded by beautiful objects. I had the opportunity to contemplate his universe, objects that inspired him, pre-Columbian pieces, his own sculptures, his paintings, wooden constructions of abstract human figurines and animals that brought out the cuteness, the anima in them, his extensive work in different materials and dimensions that focused on the symbolic abstraction of the primordial force of Nature, the beginning and the evolution of man and his environment.

I had first-hand opportunity to see the process of his work, of how he brought out the essence of easily recognizable, every-day objects, and transformed them with a sharp understanding of harmony, unity and plasticity, a selective range of hues and tones of bright earth colors, and see how their symbolic and archetypes of shapes, geometry and proportions freely morphed into new creations.

I had never met an artist so well informed of the world around him. He knew all the news, political conflicts, wars, latest scientific and health inventions, celebrity gossips… and yet he was imbued in the concrete reality of being human, and never for a second abandoned art tradition and the timeless universal structures of truth.

With a great sense of humor, he used to tell me stories of his models and lovers, of beautiful women and art, of how he had conquered his wife, Joana Simoes, who had been engaged to be married to a Nobel winning author. We talked about everything, because to him, art was everything. He was approaching his 90s, and one day he told me with much zeal and excitement that he had discovered the poetry and structured rhythm in hip-pop music. “I have been listening to it all the time”, he confessed to me in a low voice.

He also taught me. Every time he saw me struggling with lines and composition, he would stop me, and say, “don’t complicate your life. Simplify it, not complicate it; remember to have the fun”. However contradictory it appears to be, art as labor and devotion is in reality simple and fun, and above all, free; it is a labor that involves a free connection with everything in the universe.

One day he fell ill and was taken to the hospital. I remember that as the nurses took him into his room, he pressed a book of paintings tightly under his arm as if his life depended on it. It was a book of paintings by his teacher, the Uruguayan old master Joaquin Torres-Garcia, founder of the Universal Constructivist Movement.

As an artist who labored tirelessly for the traditions of art, he also said these words once, as shown in the notebook of one of his disciples, Marcelo Larrosa Martinato : “The artist should be humble and accept the world of today”.

Now that these words echo in my mind, I feel that not only was he humble enough to accept the world of today, but somehow the world of today is shifting towards bygone traditions and is taking the opportunity to accept, or rather, salute and remember and, once more, learn from Julio Alpuy’s labor in this timeless, infinite terrain of art making.

*Image on slider – photo by Alvaro Zinno.