From the Series of Essays Ritual Practices by Elaine Smollin

It’s common to see the ideals we project through visual means fall away from their central aim, which is, to provide a testament to life unmediated.

And so it is, that if an image fails our abilities to provide its abstraction, the conditions we depict are rendered irrelevant. That irrelevance has its profound prosaic forms that threaten to alter forever the conscious awareness that the arts of perception give us. To make images relevant is to make them as believable as actuality.

As far removed as the pictorial aesthetics and political transformations of mid-twentieth century may seem, their bright essence and dark shadows still cast vivid desires to press the challenges of convention and experimentation further.

Let’s choose fifty years ago as a demarcation point for the pictorial heritage of perception and imagery production, 1964-2014. We’re now long past the tipping point of when styles of perception in America expressed lived experience as the cultural properties of people of the Americas and Europe.

Everywhere today we can admire the new world demographic in which, who history has made of us, is now unfolding at an astonishing rate. We can see precisely how the arts of perception regarding land and its image as artifact have evolved through legacies of visualization across the past fifty years in the exhibitions of Ying Li and Stanley Lewis this fall.

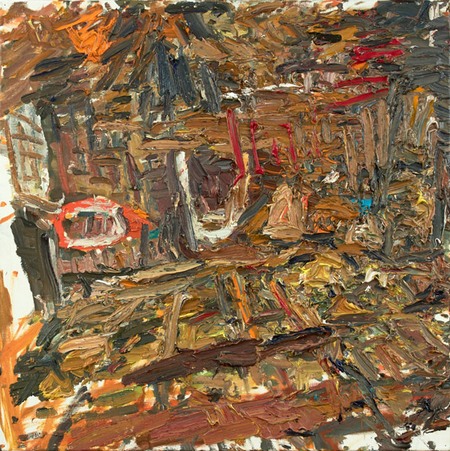

As if to refresh our awareness of these inescapable processes Betty Cunningham’s new gallery at 15 Rivington Street, opens the season with painting by Stanley Lewis through October 25. On October 28th, Ying Li’s exhibition opens at the Painting Center through November 23rd.

If you enjoy the phenomenology of perspective/perception, Betty Cunningham’s new headquarters, is a perfect space to see the arts of perception engage the evolution of painted images from the act of seeing to materialization. Paintings look so well actualized there, their impact so immediate, that the long philosophical symbiosis between mid-twentieth century film and painting rushes suddenly to mind.

It was in 1964 that Bernardo Bertolucci released his second film, Before the Revolution. In it, perceptions and historical forces ply their way through characters’ lives. Bathed in incandescent light, landscapes unfold as the forceful primordial witness to multiple forms of visual and narrative climax. Characters’ competing sensibilities stubbornly run their course, to untangle their fates from external perceptions, revealing as many twists as there are variations in our origins, opinions and desires. All the while an elderly man paints at the riverbank, observing the phenomenology of light, the passage of time and the eternal nature of a large stream.

As the film illustrates, one clear path to end points of history seems to emanate from within fissures within tradition and opinion. The actors demonstrate how gradually our perceptions meld with new shifts in consciousness as generation ’68 and generation ’48 attempt to prepare themselves for the future. The beauty of this film, owes its aesthetic wisdom to Aldo Scavarda, its cinematographer, who also shot Antonioni’s L’Aaventura, four years earlier in 1960. These films evoke the material and philosophical dimensions of land and architecture that painting can compete with evermore.

Like paintings of that mid-century, Before the Revolution broods over the destiny of society after multiple cataclysms and the rapidly vanishing physicality of land. As disillusionment prevails, hopes in sustaining personal attachments to landscapes and regions that are inextricably linked to soul and identity are lost.

The land, the painter, the water play on however as if in tune with an inextinguishable form of knowing, that occupies a higher plane of alerity than any experience mediated by society and economy can reach.

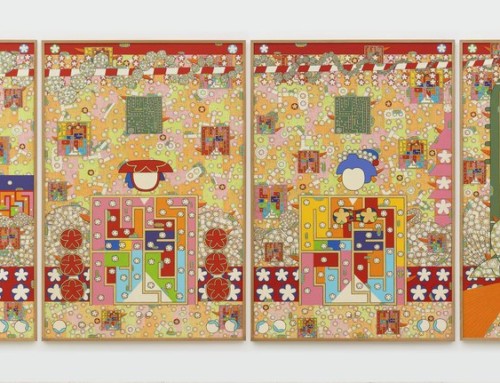

Likewise, painters Ying Li, born 1951, Bejing, China, and, Stanley Lewis, born 1941, Somerville, New Jersey show how the material and experiential aesthetics of visualization reflect where it is we stand within the function of perception in American society today.

Their orientations and attitudes toward material and matter may depend on the force of climatic presence for their clarity. Yet, their physical means to convey the singular authenticity of living a scene, on site as they do, is obtained by placing the primary structure of seeing through tactile synthesis of light and time as if within our reach.

Surfaces bound together in Lewis’s drawings and paintings remind the viewer that the intelligible world, that of his period dwellings and an irreducible Americana-world are really a hand-made puzzle, made to endure successive generations with or without any consent to the persistence of this period design and decoration.

Small boats, likewise, perch on land as if indifferent to historical associations with watercraft of Impressionist paintings, that are are pretty, rather like girls’ dolls, that bear no significance to womanliness. Instead, Lewis boats cast a fine line of tension between facts of perspective and reflected shadow to project a metaphor between the primary task of rendering the real here and now, as an extension of the external spirit of that thing as a prototype for human being in the world. We see its transitory nature more intensively than we notice its identifying features.

Ying Li’s paintings exert one of the finest antidotes to recent trends in paintings that result from effects via graphic design programs, those formulae of artificial vision that expose critically seen realities nicely. As visceral as the practice of that kind of thermal layering can be in the production of paintings and films, it is ultimately design by device, not decisive seeing out in the world.

Li has a wonderful tendency to meld the metaphysics of form to image. Binding color to intricate spatial relationships, leaping aside references to Auerbach or Kossov, she lifts the edge of forms sufficiently off their plane to accelerate how it is we estimate the volume of pictorial space. As she alternates compression and expansion of the picture plane, it could be 1964 all over again with Hans Hoffman on the cover of Art Forum but in this scenario, unlike then, we’ve seen all the Bonnards, Noldes, and Kokoschkas that came into public view here in the States.

Art historical references may be set aside from both Lewis and Li since their visions, so alike in material presence, use depiction to arrest and defy stylistic legacies. They dwell clearly in the present.

*Image on slider: Stanley Lewis, Hemlock Trees Seen from Upstairs Window in the Snow, 2007-2014 Pencil on Print Paper68 3/4 x 59 3/4 inches.