by Jairo Dueñas

The Colombian artist Male Correa wadded into the dark God-forsaken recesses of the city of Medellin, determined to paint them. She opened the doors to the slums and surprised their seemingly spectral inhabitants, illuminated their run-down spaces, spelled out their messages, painted their objects, and showed the aura that exhaled from their wounds.

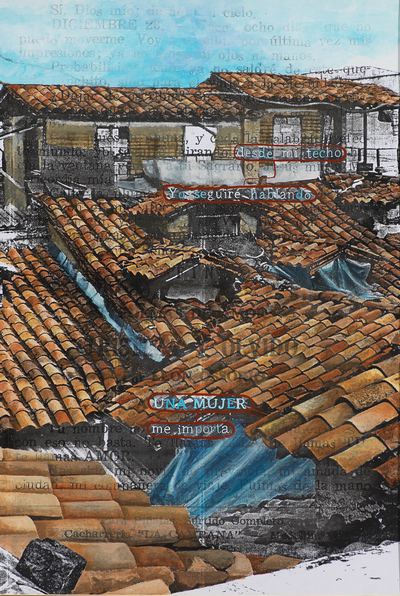

Male Strolling Down Guayaquil, a slum in downtown Medellin that has inspired the artist to make her paintings

Just like the way drawing books ask children to find a hidden figure by following a succession of dots, our lives make more sense as we tie together the different destinations mapping out our search. The rest is left to chance and to the colors that we fill in.

In the case of Male Correa, the lines of her drawings started when she chanced upon the old and low-income housing of Guayaquil in downtown Medellin as a college student of graphic design working on her thesis. She was attracted to the aesthetics of urban decadence, of dumps like bars, canteens and dilapidated rooms for rent. “An ugly place, dirty and dangerous, but to me, it is beautiful for the colors, textures and deep wounds”.

From then on to now, 30 years later, from being an illustrator to a painter, she has never stopped feeding her photo archive and collection of found objects in that decrepit quarter, a permanent well of her creation.

“All my life”, Male explains, “I have been interested in the denizens of those slums…How is it possible that a group of prostitutes, junkies, drunks, and displaced peasants can form a family capable of sharing these ruinous spaces!”

Looking at her paintings feels like entering the mindset of an observant five-year-old who used to travel aimlessly by bus every Sunday all over Medellin next to her mother, her twin sister, and her brother, with the sole purpose of contemplating through the window the crowded procession of pedestrians and a parade of building facades.

To understand her, I have put aside her art and asked about her childhood and her father. She only met him when she was 26, when she learned that a prestigious visiting lawyer from the capital city of Bogota had turned out to be her father.

She lived with him in the final years of his life (from 67 to 73 years old). When he died, she finally understood what she was actually looking for in the old Guayaquil quarter; it was her father and the frightening reality of his absence.

For Male, her voice as an artist, her intention, is to stay in Guayaquil. Her recent series, “Basic Needs”, is inspired from a conversation with a homeless woman who, from her abject poverty, had approached her to tell her that she had taken a shower and was eating every day. The proud tone of the woman took the artist (following the Chilean economist Manfred Max Neef and American psychologist Abraham Mashlow) to prioritize fundamental human needs. An exploration of the space for the sake of the space, in search of concepts like belonging, identity, protection, expression and transcendence. Her interest is focused on the more specific, more conceptual, like the image of the Virgin Mary above a bed, or a signboard written in anger on the dirty shadow of a mirror that is no longer there.

Leave something to chance

The autobiographical load of her work is obvious in her exhibition “Recovery” in 2008, which opened after she stayed in bed for six months to recover from a car accident that injured her spinal cord. This time, her paintings on Guayaquil reveal the agony or the resurrection of broken things long forgotten. Her attention has become more centered, she now points with a finger.

By 2011, she continues to work on Guayaquil, and this time, imaginary helicopters hover over the quarter. At times she gets out of her canvas and draws and paints in acrylic on plastic tablecloths. Her work “Humanitarian Aid” echoes victims of natural disasters whose gaze linger on their familiar spaces being covered by winter floods.

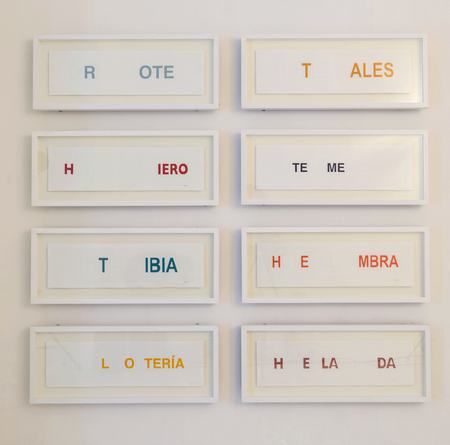

Her exhibition “Accommodations”, in 2013, decants a collapsing universe of the sick and the poor in Guayaquil. She takes one name from those bleak shelters, engraves it, puts color on certain letters and creates new meanings. “If you read those letters”, she said, “you would understand what is going on in those places…but I no longer show it, I just insinuate”.

Then, Male pondered on three questions: Who am I? Where do I come from? Where do I belong? This led her to paint freely on industrial wastepaper, much like the paper used by seamstresses to make their stitching mold. Thus, emerges in 2016 her homage to the Colombian poet Manuel Mejia Vallejo, “Maleducaos recuerdos” (Undereducated remembrances), in which she first draws a line of the poem with honey and then spreads graphite powder on it, allowing the line to erode and fall into imperfection. The page has ceased to be a page, it is now the complexion of a woman and the letters melt away just like how her make up is dissolved by her tears of bitterness.

In 2018 Male’s work at last gets the recognition of the National Cultural Awards of the Antioquia University. Her pictorial language has attained an identity. Male smiles and reflects on being original: “In this arena they call for an original voice, which is a compulsory requirement, and when the artist at last gets it, the same choir criticizes her because she repeats”. They look for unique creative voices, one that would live on, and yet they forget that authenticity in art is self-destructive

Those who are always seeking do not want to repeat themselves. And this artist does not stop seeking. Her father, the drive for her search, no longer lives, and yet to find him in people that crosses her path is a comforting exercise of humanity. She is aware of that, she simply awaits on street sidewalks for a tremor, a gesture, a sign.

For her current exhibition “Semejante” in Medellin, the artist decides not to bring her work on delirium to a gallery space, so she locks herself up with her paintings for one whole month in a house about to be demolished. Behind the ruins of those white walls, Male succeeds in finding a most perfect way to highlight the anonymous life that lingers in her paintings. For her, her art is a mirror that breaks, silences, sings and shouts out loud.