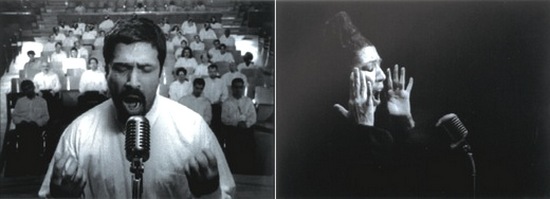

The woman on the screen is in a completely empty auditorium. She is singing and her voice is shrill and long, like a wounded animal. In her voice there is also a yearning, a pleading, as if she were praying. At the same time an immense tenderness is felt, as if her song were a declaration of love.

In front of the woman there is a second large screen. On the screen we see a man also singing. His voice is also visceral and behind him there is a full audience.

The two screens are faced to each other, and the viewer is placed between them. One feels that the man and the woman were looking at each other and addressing their voices to each other, completely oblivious of their respective audiences.

“Turbulent” ( 1998) is a 10-minute two channel video installation by the contemporary Iranian artist Shirin Neshat, as part of a trilogy of moving-image works that explores the voices of veiled women within the Iranian society, where women are not allowed to sing in public. The film is staged and filmed in New York and played by the well-known singers Shoja Azari and Sussan Deyhim.

As an Iranian female artist living abroad, Neshat has witnessed with both “fascination and horror” the events that have impacted Iran in the past 30 years, and her work inevitably reflects the county’s turbulent social and political transformation. Her most representative works are put together for the first time in a major retrospective exhibition called “Facing History” recently held at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D.C.

It is interesting that the show was held at the capital city of the United States at a time when the controversial U.S-Iran nuclear deal was made .

One might immediately misconstrue her work as solely political, and yet if you spend time and look at the progression of her work, you would see that her historical commentaries go beyond the political and extends to more profound and intimate issues of human love and relationships.

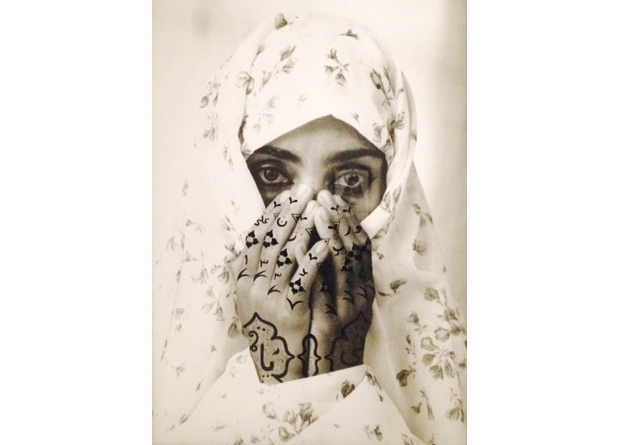

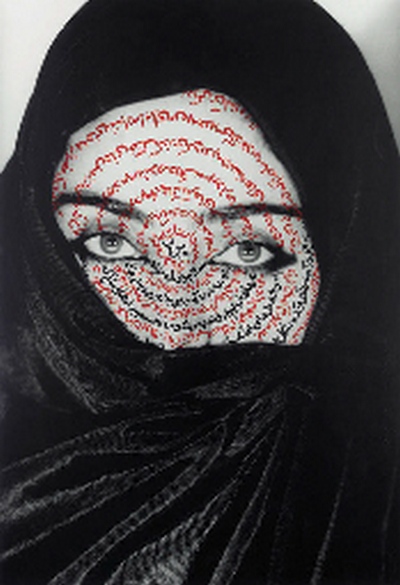

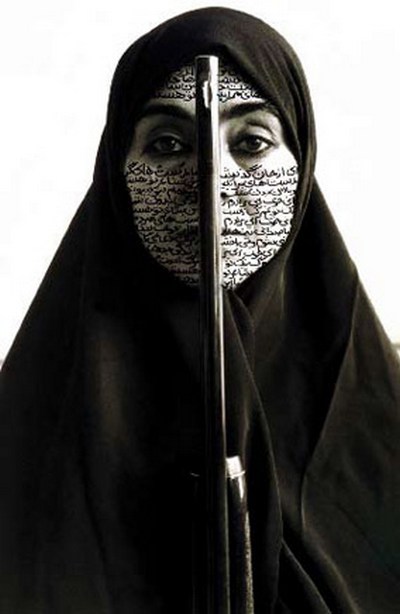

Rebellious Silence, 1994, from the series of Women of Allah, Ink on RC print, photograph by Cynthia Preston

It is obvious that Nesha’s work also reflects her interest in showing women as a source of strength and awareness, although they are not considered as major players in their society’s socio-political evolvement.

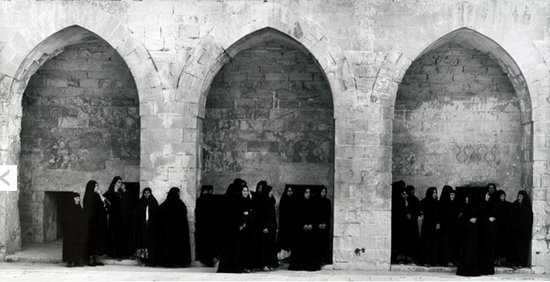

The second film of the trilogy is called Rupture (1999). For 13 minutes, the viewer is again placed between two large screens, showing the parallel worlds of men and women. Neshat directs the performance of 100 men and 100 women in a stylized mass choreography; the men wearing white shirts and dark pants, and women with black chadors.

In the film the men stay within the confines of a medieval fortress, whereas women eventually break free and go for the open space of the sea, some of them, manage to launch a small boat into the water.

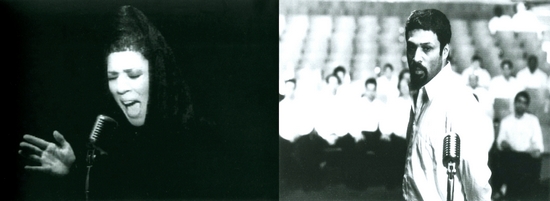

The third film, Fervor (2000), is a bit different from the two previous films. This time the two large screens are placed side by side. The images focus on a woman and a man, and in the first scene their paths meet as the images converge and overlap. Then they enter a room to watch a lecture on the danger of sexual temptations illustrated by the parable of Youssef and Zoleikha, a story from the Koran adapted from the Old Testament. In the room men and women sit in two different crowds, separated by a curtain.

As the performance of the lecturer grows in intensity, it is the woman who stands up from the crowd and leaves, and the man remains on the other side of the room, wondering about the woman.

The images of the separation between men and women as a result of religion and other beliefs stir a feeling of loneliness and incompleteness for both men and women on equal measurement. Although it is not explained in the film, one cannot help but feel a stifling sense of truncated intimacy and personal development.

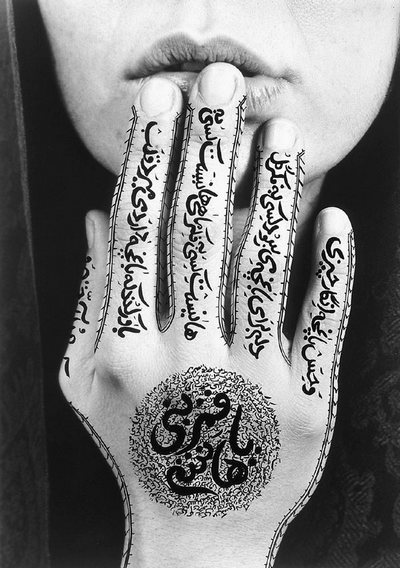

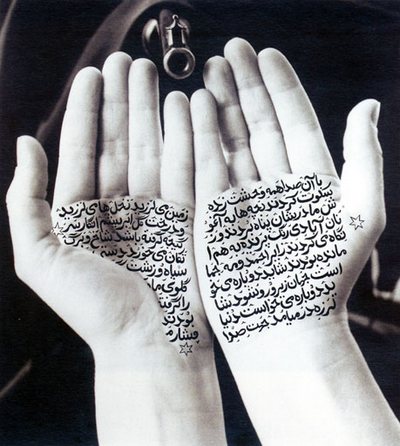

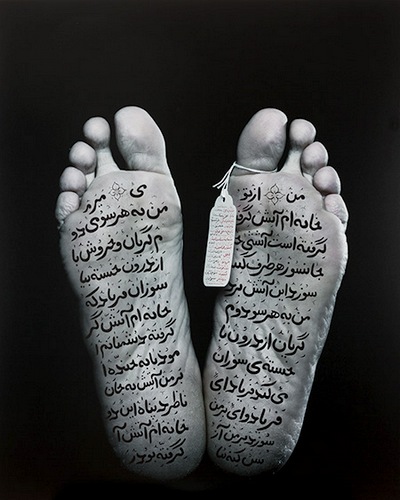

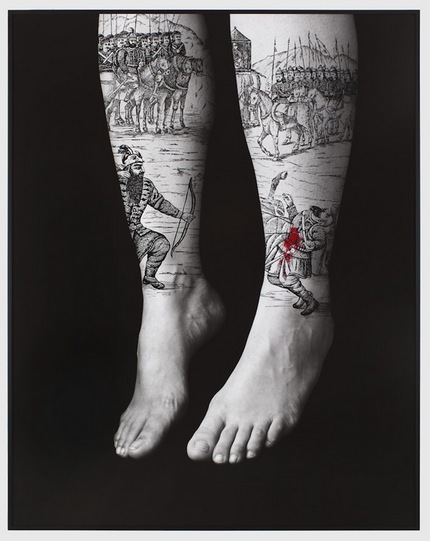

For example, her 1993-1997 series of photos, called “Women of Allah” shows impressive images of veiled women often posed with weapons and defiant stares; and on their bodies, symbol-like Persian texts are inscribed. The texts are not tattooed on the women’s body as one might think at first glance; they are actually handwritten directly on the surface of the photos. They are not religious, they are extracts of Iranian contemporary poems.

Allegiance with Wakefulness, 1994, from the series Women of Allah. Ink on RC print, photograph taken by Cynthia Preston

In “Offered Eyes” ,for example, we can clearly see how the verse of “My Heart Grieves for the Garden” by the Iranian female writer Foreough Farrokhzal, is inscribed on the photo of the image of a woman’s eye.

In the series of Munis and Revolutionary Man (2008), Neshat uses the perspective of her main character, a young woman named Munis, to show the political development in her country since 1953. The series consists of photos and videos that follow the narrative of a magic realist novella written by one of the most widely read female authors, Shahrsush Parsipur.

Soliloquy, 1999, Two-channel video installation. Color. Sound. Running time: 17 minutes, 30 seconds, director: Shirin Neshat, in collaboration with Shoja Azari. Cast: Shirin Neshat. Writers: Shirin Neshat and Shoja Azari. Director of photography: Ghasem Ebrahimian. Composer and sound designer: Sussan Deyhim. Producer: Barbara Gladstone. Filmed in Turkey. Shot on 16mm color film.

In Soliloquy, 1999, a two-channel video installation, Neshat places herself as the main character traveling through radically different landscapes of culture and community. For 17 minutes we experience through the artist a journey of introspection of self and identity, and her creative life and vision.

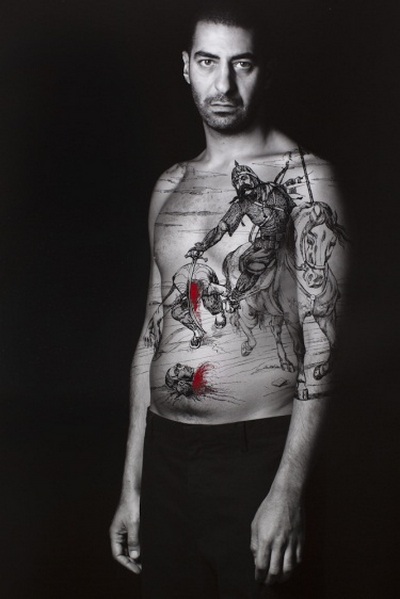

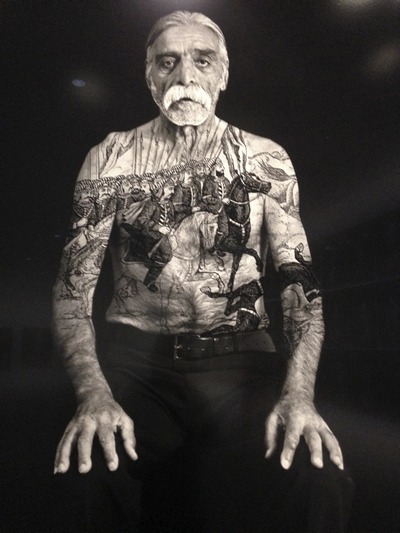

Villains, from the series The Book of Kings, 2012, Ink on LE gelatin silver prints, photograph taken by Larry Barns.

In the large scale work of The Book of Kings in 2010, she shows enormous photos of people’s faces in reference to the Iranian epic book of Shahnameh , a collection of 50,000 rhyming couplets written by poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi (c.940 to 1020), that narrate the story of pre-Islamic Iran, proceeding Monarchy, from the creation of the world through the Arab conquest in the 7th Century. A literary feat that has often been compared to the Homer in the West , filled with stories of war, love, heroes, kings, monsters…

Bahram, from the series The Book of Kings , 2012, Ink on LE gelatin silver prints, photograph taken by Larry Barns.

Neshat has copied some of the illustrations of Shahnameh and incorporated them into some of the photos in an attempt to capture “the rise and fall of the narratives of political upheaval, revolution, patriotism and tyrants”.

In “Our House is on Fire”, commissioned by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Neshat works with photographer Larry Barns to shoot faces of people following the Egyptian revolution of 2011, reflecting the human cost of political upheaval.

The subjects in the photos are people from the sites where the revolution took place. They were willing to sit for the camera and at times share their personal stories of loss. A fine veil of writing is often found on the photos to meld with the creases of the faces of the subjects.

My House is On Fire, 2012, excerpted from The Book of Kings. Ink on LE gelatin silver print, photograph taken by Larry Barns.

The writings are poetries on death, grief, and defeat by an array of Iranian authors including Forough Farrokhzad, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Ahmad Shamlou. The title is adapted by the first line of the poem by Akhavan-Sales.

Neshat’s exhibition is epic and literary. Watching it feels like watching history evolve, so the title of the show is justified. However, we have also experienced a tremor of deep human sensitivity about big political issues, which perhaps can be best described by these lines that we found in one of the books of Iranian poets in the room adjacent to the exhibition:

Everyone is fearful

Everyone is fearful, but you and I

joined the water and mirrorand light

and were not afraid….

Fervor, 2000, Two-channel video installation. Black-and-White. Sound. Running time: 10 minutes. Director: Shirin Neshat, in collaboration with Shoja Azari. Cast: Mira Ghamsari, Houshang Touzie, Mohammed Ghaffari. Writers: Shirin Neshat and Shoja Azari. Director of photography: Ghasem Ebrahimian. Composer of sound designer: Sussan Deyhim. Production designer: Shahram Karimi. Editor: Bill Buckendorf. Line producer: Hamid Farjad. Producer: Barbara Gladston. Filmed in Morocco. Shot on 16mm black-and-white film.

* Cover image: Shirin Neshat – The Height of Wakefulness from the series Women of Allah

* Image on slider: Shirin Neshat at the Hirschhorn Art Museum in Washington, DC – Photo by Jim Watson, AFP