By C.C.

If the soul has a language, one would most likely find it in a painting or a sculpture by the Uruguay-born artist Joaquin Torres Garcia (1874-1949).

As I watch the exhibition The Arcadian Modern, currently held in Spain, I cannot help but arrive at this conclusion.

It is perhaps the most complete and significant retrospective of Torres-Garcia that I have ever seen. Organized by the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), the show first opened last year in New York, then it toured to the Telefonica Foundation in Madrid, and it will be on view at the Picasso Museum of Malaga from October 11 to February 6, 2017.

Much has been written about the so-called “eclectic” look of his paintings and yet no one has been able to set aside the extraordinary language that he created during the historic time of two world wars; global economic depression; extreme manifestations of violence, racism, and political resolve; and the messy advent of weapons of mass destruction. It is not hard to presume that soulfulness has eventually elbowed through chaos and confusion to manifest at last in the form of art, a constructivist art that does not conform only to beauty, but also valiantly fulfills the goal of communication at deeper levels of the human psyche.

The interesting point here is that the awareness comes from an artist from the Southern tip of the American Continent, a country called Uruguay, known for several internationally recognized poets and writers, and a somber landscape of the sea. Torres-Garcia famously reversed the map and turned Uruguay to the North, perhaps to illustrate the mythic concept of sacred geometry “as above, so below”, or as largely stated, that South is actually North (referring to the Northern Star) of the continent.

The show displayed more than 170 art works, including paintings, sculptures or what the artist called “constructions”, drawings, collage, and frescos. The art historian, poet and curator Luis Perez-Oramas was appointed by the Museum of Modern Art in New York to organize and carefully put together the artwork from at least 70 collections, both public and private, from different parts of the world.

The exhibition has four sections, each showing a chronological period of the artist’s work according to the places that he lived. It begins with his years in Barcelona (1891-1920), when at 17, Torres-Garcia got involved with the vanguard Modernists of Noucentisme, a Catalan movement opposing the “sophisticated decadence” of art nouveau, and promoted art’s relationship with nature and primitive history.

Jouets transformables Aladin, 1930

Conjunto de juguetes, painted woodblock, size varied, box: 14x28x3 cm

From the beginning his approach to Modernism was different from most artists, since he introduced classical figures into a modernist style, and in 1916 received severe criticism from intellectuals of the Academia.

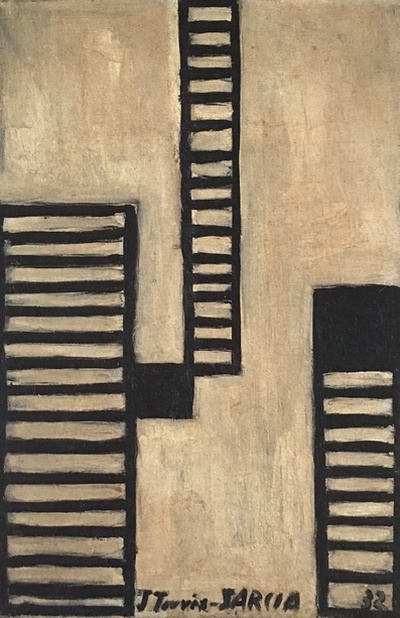

In these early years, his work showed a search for new style of representation, in which planes and figures were juxtaposed, flattening more and more the surface, reaching new depths with the emphatic use of verticals and horizontals, such as his Vibrationist Compositions (1918).

In 1920, Torres-Garcia moved with his family to New York, to a new continent of Modernism. He quickly blended into the art circle and produced a series of toy like wooden sculptures that he called The Aladdin Toys, with them he proposed a concept of transformable sculptures, which could be composed or decomposed. The exhibition reserved a special space to show several pieces of the toys.

In this brief period in New York, one could detect in his paintings an excitement for the crowded urban landscape and architecture, and an accelerated energy towards progress and cosmopolitan sophistication of the Big Apple.

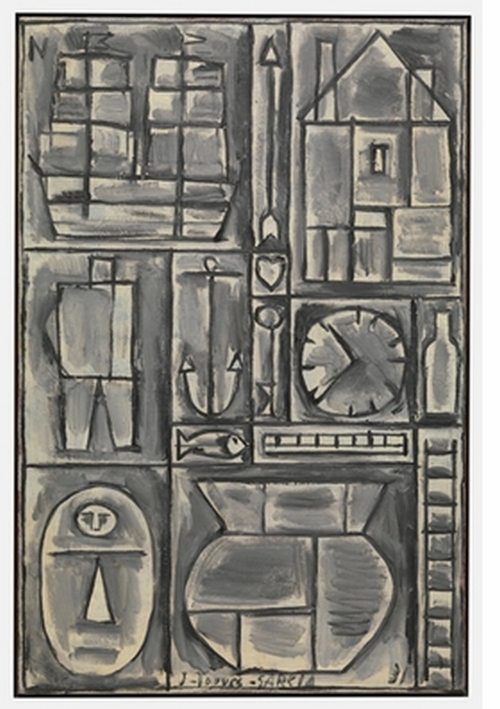

In the period of Paris, 1926-1932, Torres-Garcia worked and wrote extensively, delved into issues of primitivism, and the incorporation of representational figuration into a modernist approach. He did not follow the Constructivist path of his friends and peers like Piet Mondrian and Theo Van Doesburg, who chose a style of pure abstraction. In many of the works of this period, we find an imagery structured with archetypes of easily recognizable symbols of daily life objects, such as the clock, the fish, the coffee cup, the stars, the heart, the spiral, the ladder, the balance, the hammer, man, woman, house…

Torres-Garcia’s modernity strangely adopts a look of antiquity. There is an apparently deliberate inclusion of the archaic, as if to allow its presence to become an issue of modernity. He built a series of painted assembled wooden structures called Objects Plastiques, showing different strategies of three-dimensional formal compositions to prove his concept.

In the section of Montevideo (1934-1939), we can see how his work evolved as he returned to his homeland of Uruguay. A group of synthetic and concrete abstraction works reflect a confident use of a new language that he created called Constructive Universalism. They have an increasingly structural image, with a reduced chromatic tonality, and an organized, proportional progression of dimensionality in terms of planes and forms, and yet inclusive of the abstract resonance of the archaic, and sometimes, pre-Columbian mysticism.

This language called for the creation of an authentic movement of Latin American modernism, independent of the European movement. The evolution of art, led by this regional awareness, is a universal one, with a universal purpose, one that goes beyond historic and cultural guidelines and barriers.

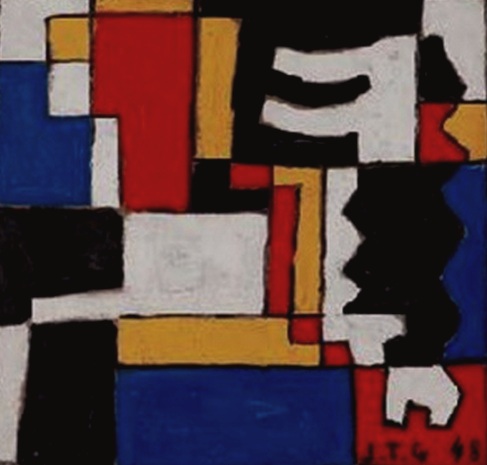

At the end of his life, his work returned to the use of intense colors, especially primary colors, which appears to have acquired a tonal purpose. One can see that clearly in his painting “Structure in Five Tones, with Two Intertwined Forms” (1948).

His last work, Figures with Pigeons (1949), is an oil painting on cardboard in tonal earthy color relationships, and geometrical forms that look like the classicism that he first approached in Barcelona, but more playful and concrete, showing a simple familiar scene with a woman holding her baby in her arms, a particularly moving image showing the simplicity of the human experience in a reductive, unfussy, undramatic, and honest way.

In a way, I have found that all the works of Torres-Garcia during all these different periods of his life in different places of the world exudes a rare quality of inclusiveness. The harmony and proportional perfection that are felt in all of his works do not seem to pursue a single minded perfection; they are often child-like, unfinished, humorous and serious at the same time, vibrant, detached and yet kind and empathic; monochromatic and yet festive and unexpected.

Seeing this show, for me, is one of those rare occasions in which one has encountered with an extraordinary artist through his work. In this encounter, I feel, that I actually had a conversation with Torres-Garcia and the elements of time and physical reality were irrelevant. After I left the show and Madrid, I have been constantly reminded by the message of his work that I perceived during that conversation, that a universal language of art is free, knows no boundaries of geography, time or dimensionality; it is always contemporary and it has endless possibilities.