An afternoon visiting photography exhibitions around Beijing can take you to a China that you have rarely seen, surreal landscapes on the earth’s far flung places, and the contrast of men and machine inside a French car factory in the mid-30s.

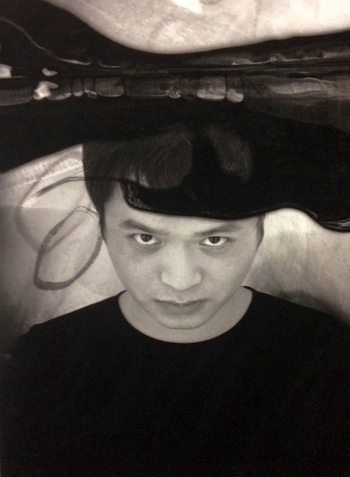

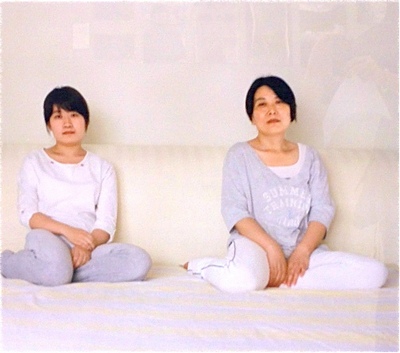

Three Shadows is the first contemporary art space exclusively dedicated to photography in China. The spacious gallery sits on a former auto repair yard and was designed by renowned Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. This year’s 6th Annual Photography Award Exhibition prizes new trends and techniques from a selection of 580 works submitted by Chinese contemporary photographers. Of the 28 awarded, Wang Yaxin’s work consists of a series of mothers and daughters whose similarities become apparent when they are asked to sit with the same pose. Wang Yuanling, another awarded photographer, depicts men’s cruelty towards nature and tells us that the earth provides men with life and “when we die, we give our soul back to the soil”. Ma Che’s portraits are taken in a most unusual way. Through the Internet, he asks people to collect their own garbage for a week and send it to him. He sorts out the perishable waste and buries a roll of film in it for one week, after which he lets the film dry for another week. He then visits the owner of the garbage and uses the film to take the portrait. LI Shun’s work was not awarded but it is interesting. From far, it looks like Chinese calligraphy but the symbols are in fact meaningless and are made from abstract photos of Hangzhou’s alleyways (detailed street names are listed at the lower end of each piece).

At the +3 Gallery, Zhang Kechun’s solo exhibition consists of photos taken at the banks of the Yellow River, China’s longest waterway also known here as the “cradle of civilization”. Mr. Zhang is in his mid-30s and uses a large format Linhof camera. His interest is in environmental destruction. His faded photographs are of ordinary people doing ordinary things, microscopic figures against a gigantic backdrop of construction or destruction. For the shot of the swimmers crossing the Yellow River with a photo of Mao Zedong, he had to go back several times to the small village because this annual event takes place unannounced.

Recipient of numerous prestigious awards, French photographer Emmanuel Coupe-Kalomiris’ “Aerial Series” at Meridian Space seems to come from a fantasy world. Taken from high above the clouds in southern and central Iceland, they show fantastic formations of the atmosphere and abstract color pallets of the land below. Such landscapes are formed by fire (volcanic activity) and ice (icy cold weather) and Emmanuel vividly captures these two opposite elements at work.

In the ancient surroundings of a Buddhist Temple at the Temple Hotel Gallery, Robert Doisneau, one of the most celebrated French photographers of the modernist era, offers the public a rare opportunity to see a major exhibition of over 70 of his black-and-white photos. Known as the pioneer of photojournalism and humanist photography, Doisneau’s “The Kiss by the Hotel de Ville” marked a most moving and indelible moment of history with the image of the passionate kiss of a young sailor and a nurse during the celebration to mark V-J Day, the end of World War II.

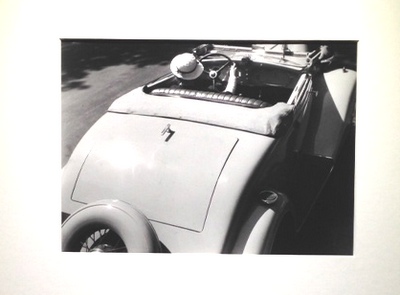

Doisneau began his career as an industrial advertising photographer at the Renault car factory in Boulogne-Billancourt. Though trained as an engraver, Doisneau turned to photography in his early 20s when he became interested in capturing the ephemeral nature of light. He embraced the modernist visions that emphasized dynamic lines and new angled perspectives, the “sincere” or “slice of life” photography launched by the German magazine BIZ (Berliner IllustrirteZeitung) and then LIFE. But the equipment provided by Renault fell short of these technical advances and he had to “manage with obsolete, imprecise equipment…For example, there was no shutter. Instead, we used a hat that we put in front of the lens”, Doisneau recalled.

Instead of showcasing the Renault cars only, Doisneau gave equal importance to its surroundings, blurring the advertising aspect and enhancing the art form. When he first started to work for Renault at the age of 22, he knew nothing about the world at large, the car industry or the advertising scene.

With his curious eyes, he was able to capture contrasting lives, that of the high society populated by models and moguls and the daily toil of the Renault workers. “I was rather shy with the workers, bosses and lords of the factory,” Doisneau later said.

His fascination with men and machine can be seen by his repeated portrayal of a lone worker against humongous industrial machines.

*Cover photo: Miss Paris in Cabriolet by Doisneau.