If you do not know that this is an art installation, you might think that this is about procrastination. But it is more. The Refusal of Time is an invitation to meditate about the issue of time. Drawn by the curious title, we went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and saw the 30-minute five-channel sound and light video installation, created by the South African artist William Kentridge. Situated in a dark room at the end of a hall on the museum’s second floor, one could hear a coherent sequence of indeterminate sounds and music long before reaching there.

Once inside the room, we found ourselves in a world surrounded by wall-size video images of metronomes pulsating incessantly on five huge screens while tuba tunes vibrated in gradual crescendo. In the middle of the room, there was a huge wooden sculpture of some kind of a machine, moving mechanically under a dark ghostly light, and among the shadows, it felt as if it were throbbing, as though inside the belly of a huge clock.

There were around 20 chairs sprawled disorderly in the room. Those people who could not find a seat, just stood there, looking, some of them laughing, or giggling, others sat comfortably on the floor.

Kentrige’s approach to the issue of time was direct and to the point, without beating around the bushes even in its most subtle moments of socio-political implications. We felt that he delved further away from a simple critique of the historical evolution of time, and was more interested in reflection and the abstract experience of time.

The heightened drama of the installation was supported by a paraphernalia of rich references, ranging widely from literature, science to animation and cinematography.

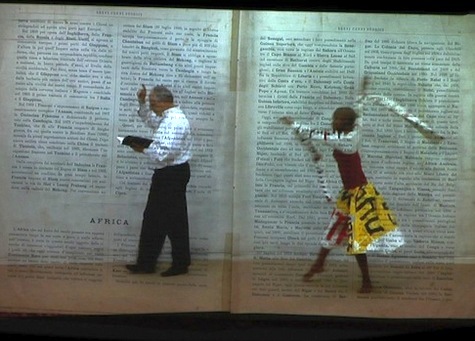

From different angles, the installation offered an epic experience. One sequence of images captivated our attention: the artist moving around in different spaces, and suddenly he was on the space created by his own charcoal drawings, giving us the impression that the lines were drawn to define time while time slipped in and out of reality.

Although some images promised a narrative of a particular story, they never developed into a complete plot, like in a movie or in theater; they stayed in the realm of subtle aesthetic implications.

We saw moments of European colonialism, newspaper clippings denoting human violence and rebellions, maps of the world, words showing pathos of hopes and despondencies, doing and undoing of events, a parade of silhouettes of individuals weighing down on one another as if they were in a celebration or a funereal process, and dramatization of suffering and its iconography, while messages such as “bad clocks”, “give us back our sun”, popped up from time to time.

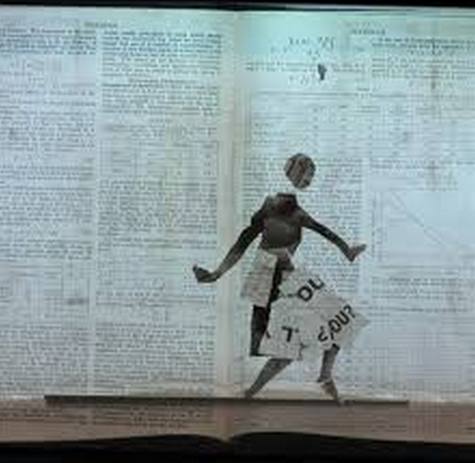

There were also poetic moments of abstract images, for example, we saw how some large black dots beginning to glue together and take form as if they were a metaphor for dust caught in the current of time as the words “the universal archive” appeared. Then the words, “he that fled his fate” and soon after, a dance began first by a doll made of newspaper, then, a barefoot black dancer wearing a beautiful white dress started to gyrate in the midst of a multitude of objects, as time evolved and devolved, and he simply continued to dance as if time did not exist, and yet was riding on the wheels of time, while everything around him gravitated into a whirl of ethereal dimensionality, into a restlessness of time…

The music was important, it was loud and brassy, and complex, and easily got us involved in ebb of a blend of emotions, awe, and reflection.

We felt we had been oscillating back and forth the pendulum polarities of Dante’s Inferno and Paradise, and were forced to address the issue of time in an experience where time seemed to have paradoxically stood still. It seemed contradictory that amidst such an excess of imagery that symbolized or represented time, one felt the non-existence of time. And at the end of the experience, when the room echoed with enthusiastic applauses, and the music began to subside, it felt good to have lost time for a moment.

The Refusal of Time was created in 2012 for Documenta 13. It was a collaboration between Kentridge and the science professor Peter L. Galison, the video maker Catherine Meyburgh, and the musician Philip Miller. According to Galison, both Albert Einstein and the late-19th-century mathematician Henri Poincaré arrived at the conclusion that time, as experienced in the modern world, is a relative rather than universally fixed phenomenon.

The installation is a recent acquisition of the museum, jointly with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

It is on view in New York through May 11.