A city gains its reputation rightfully or erroneously, but to change that perception in people’s hearts, it needs a good idea. A great idea. A monumental idea.

Miami is known for many things, a retirement paradise, a passageway for drug trafficking, a hurricane magnet. A clichéd image of sun, fun and stupidity. A cultural wasteland…until 1980, when Jan van der Marck, director of the Center for the Fine Arts (today’s Perez Art Museum Miami) made the first step to change that perception by asking artists to develop an art project for Miami. World-famed environmental artists Christo and his wife Jeanne-Claude accepted the invitation to visit Miami. After a brief city tour, they felt an immediate connection with the numerous artificial inter-coastal islands that dotted Biscayne Bay, a lagoon that runs almost 35 miles on the Atlantic coast of South Florida. In less than a month, Christo called Van der Marck to confirm that he wanted to develop Surrounded Islands for Miami and like all his projects, he would take no sponsorship, would cost no money to the taxpayers, and would be self-financed by the sale of preparatory drafts and drawings.

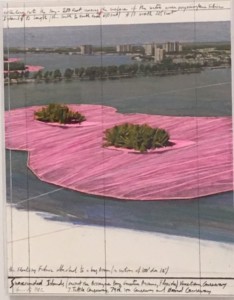

Surrounded Islands consisted of surrounding 11 islands scattered on Biscayne Bay with 6 million square feet of pink woven polypropylene fabric. The floating fabric extended out 200 feet from each island into the Bay and was sewn into 79 patterns to follow the contours of 11 islands. The luminous pink color of the shiny fabric was chosen to bring out the vegetation of the islands, the light of Miami sky and colors of bay shallow waters.

Collage 1983 in two parts: pencil, fabric, aerial photograph by Wolfgang Volz, pastel, charcoal, wac crayon, enamel paint, map, and fabric sample

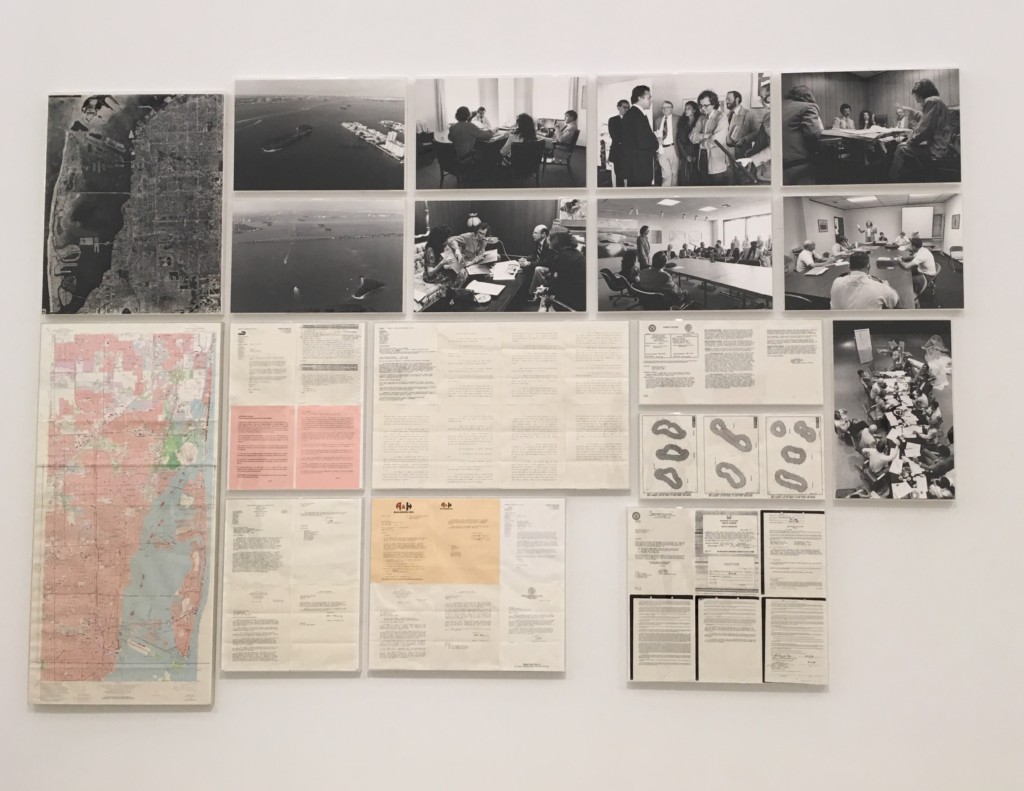

Miami in the 80s was truly the Wild West. Christo’s team spent six months of field and lab experiments to show DERM (Department of Environmental Resources Management) and protesting environmentalists that the project would have no impact on marine plants in Biscayne Bay. The team also made a censor on fish eating wading birds, picked up 40 tons of debris and refuse including refrigerator doors, tires, kitchen sinks, mattresses and an abandoned boat. Permits were needed from six different governmental agencies. Someone asked Christo to stop overworking and Jeanne-Claude replied: “It’s like asking a pregnant woman to stop pushing and have a coffee break while giving birth.” The project took three years to become a reality, but like all of Christo’s work, it only lasted briefly, and for those 21 days, it was impossible not to take notice of the pink fabric surrounding the islands from the causeways, the shores, the water, the air.

Christo put Miami on the world art map and changed the city forever. For the past 35 years, private collectors came as well as important museums including Miami Art Museum, MOCA (Museum of Contemporary Art) and Frost Museum. In 2002, with the launch of Art Basel Miami, the city became an important international center for art. This year the Perez Museum commemorated Surrounded Islands with Documentary Exhibition showing archival materials, drawings, layouts, documentation, tons of pink fabric used, and gigantic aerial photographs of tiny islands surrounded by pink fabrics by German photographer Wolfgang Volz.

The highlight of the exhibition is a documentary film by the Maysles brothers on the making of the project from beginning to end. We saw never-seen before moments such as when the Miami Dade-County Commissioner requested Christo for a sizable donation to the local government against the artist’s will and Christo solved it by offering 1,000 signed and numbered photographic images that the county could sell as posters, and the humongous efforts made by hundreds of sweaty volunteers on the islands and the boats to simultaneously pull the pink fabric to make it afloat. It is through the lenses of the Maysles Brothers that one could understand how long and arduous were the red tapes and negotiations with government officials to materialize this and various other Christo projects, including his ability to engage Jacques Chirac, the then Mayor of Paris, for the Pont Neuf project in 1984.

The exhibition, as nearly monumental as the project, has travelled to museums in such countries as France, Japan, Belgium and Switzerland before making its American debut at Perez. “Surrounded Islands is totally useless, totally irrational,” Christo, now in his 80s, said during the opening at Perez, “Art is about thingsnow, not the real thing, and Surrounded Islands was very real.”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude were born on the same date, June 13 of 1935, one in Bulgaria and one in Morocco. They met in 1958 and had been working together ever since. They flew in separate planes; in case one crashed, the other could continue their work. Credit was given to Christo only until 1994, when all their works were retroactively credited to “Christo and Jeanne-Claude”. In 2009, Jeanne-Claude died at the age or 74 due to complications of a brain aneurysm. The purpose of their art is not political, even though many would argue otherwise, but simply to create works of art for joy and beauty and to create new ways of seeing familiar landscapes. Some of their major environmental works include Oil Barrels, a 4-meter-high wall built with oil barrels that blocked off for a few hours the Rue Visconti in Paris in response to the building of the Berlin Wall in 1962; Wrapped Coast (1969), the largest single artwork ever made at the time consisting of wrapping with synthetic fabric two and half kilometers of coast and cliffs in Australia and up to 26 meters high; The Umbrellas Japan-USA (1991), the parallel installation of 1,340 blue umbrellas in Ibaraki, Japan, and another 1,760 yellow umbrellas at Tejon Ranch in southern California; The Gates (2005), where 7,503 gates made of saffron color fabric were raised along the paths in Central Park, New York; The Floating Piers (2016), a series of walkways at Lake Iseo near Brecia, Italy, where visitors were able to walk on polyethylene cubes just above the surface of the water from the village of Sulzano on the mainland to the islands of Monte Isola and San Paolo.

The sheer size of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s installations inspire awe but they do not last. Once dismantled, they disappear and leave no traces behind. However, if you were lucky to be there, you will never forget what you saw.