If you don’t like art or have never been to a museum, you probably would have still heard of Edward Hopper (1882-1967).

He is often referred to as the greatest American artist in modern times. He was a master of realist paintings and yet, he inspired celebrated abstract painters like Willem deKooning and Mark Rothko. He also inspired filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock in his Psycho, Terrence Malick in Days of Heaven, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, and Wim Wenders’ End of Violence.

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), New York Movie, 1939

Oil on canvas, 32 1/4 × 40 1/8 in. (81.9 × 101.9 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York; given anonymously 396.1941

© Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art. Digital Image. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

He is best known for his oil paintings of solitary people in urban settings. Unlike other urban or landscape painters, his work had an unusual impact on the viewer, and engaged generations of people to a vision about life and what he called “nature’s phenomena” in a most personal, subconscious, and enigmatic way.

The narrative in his paintings apparently tells a story, but a story that suggests many sub-stories in a fleeting moment of a person’s life, or a city’s life, or a landscape’s life.

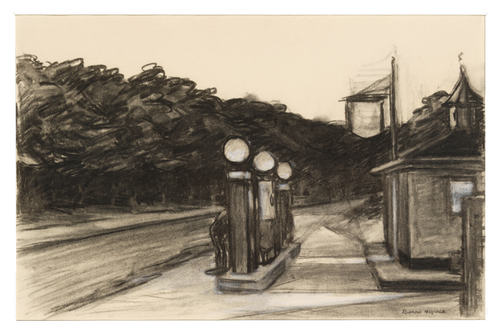

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Study for Gas, 1940. Charcoal and white chalk with graphite pencil on paper, 15 1/16 × 22 1/8 in. (38.3 × 56.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.349. © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art. Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art

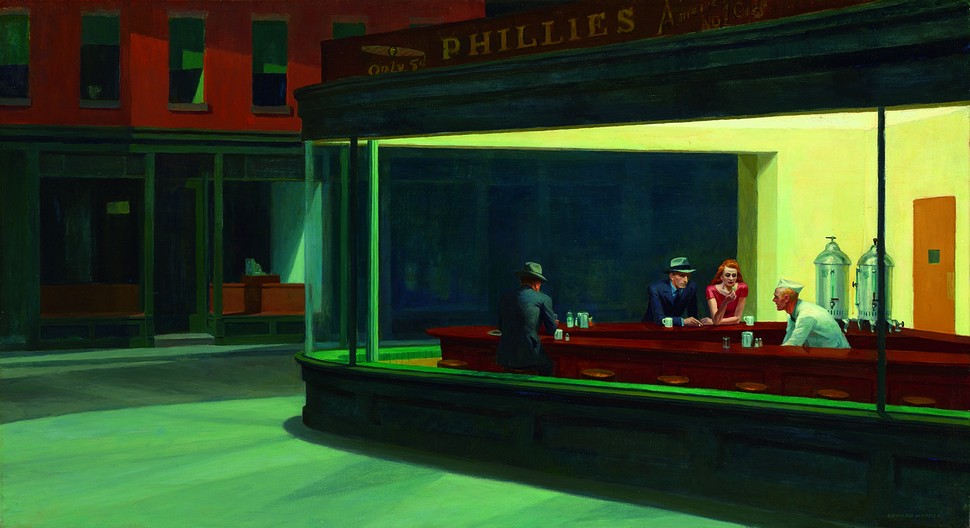

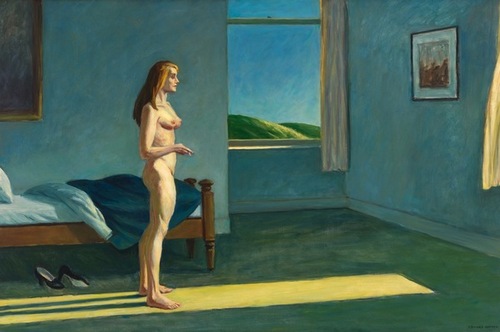

Much has been written about Hopper and his paintings, and the meanings behind his composition. But we would never really know why he painted a naked woman looking out the window, or whether or not his best known “Nighthawks”, showing a window scene at a diner with a couple-a man and a woman in red dress-, one solitary man’s back, and an enthusiastic waiter bathed in an uncanny bright and clean light in a corner of a deserted street was about loneliness.

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), A Woman in the Sun, 1961. Oil on canvas, 40 × 60 in. (101.6 × 152.4 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; 50th Anniversary Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Albert Hackett in honor of Edith and Lloyd Goodrich 84.31

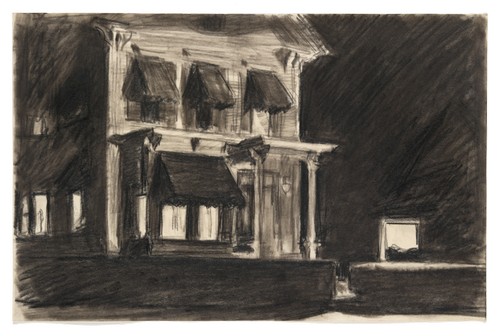

But, if we look at his drawings, perhaps we could have a better understanding of his vision. For the first time in history, the Whitney Museum of American Art has put together the most complete exhibition of Hopper’s drawings, dating from sketches of his youth to the drawings that he had made to experiment new ideas and refine content for paintings, some of them paired with the final oil paintings.

More than 2,500 drawings, many of them never researched or shown before, are currently on view.

Hopper drew both from “the facts”, referring to working from direct observation, and “improvising”, or working from imagination. By putting together his drawings and paintings, the exhibition attempts to show Hopper’s painting methods and how he synthesized precisely observed details into atmospheric scenes, geometric abstractions with concrete realism, and his distinct play of light and shadows with colors.

In real life, Hopper was known as an introverted artist who did not like to talk much about his paintings. When referring to his work, he was quoted as saying: “the whole answer is here on the canvas”. But his vision was not as minimalistic; it was more like what was reflected in his work.

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Study for Rooms for Tourists, 1945. Fabricated chalk and charcoal on paper, 15 × 22 1/8 in. (38.1 × 56.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.848. © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art. Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Study for Rooms for Tourists, 1945. Fabricated chalk and charcoal on paper, 10 3/8 × 16 in. (26.4 × 40.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.438. © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art. Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Rooms for Tourists, 1945. Oil on canvas, 30 1/4 × 42 1/8 in. (76.8 cm x 107 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven; bequest of Stephen Carlton Clark, B.A. 1903 1961.18.30

In 1953, he wrote that great art was the outward expression of an inner life of an artist, and “this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world”.

“No amount of skillful invention can replace the essential element of imagination. One of the weaknesses of much abstract painting is the attempt to substitute the inventions of the human intellect for a private imaginative conception.”

“The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form and design.”

“The term life used in art is something not to be held in contempt, for it implies all of existence and the province of art is to react to it and not to shun it.”

“Painting will have to deal more fully and less obliquely with life and nature’s phenomena before it can again become great.”

The Whitney Museum of American Art built an installation to recreate Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawk” inside the windows gallery of the historic Flatiron Building in Manhattan to announce its current exhibition of Hopper Drawings.

The exhibition curator Carter E. Foster believes that the Flatiron’s curved glass prow was part of the inspiration for the painting.

It is best to see the installation at night, when the streets are barren and the light effects are more real. Who knows, maybe we can even step into an artist’s imagination to experience our own story.