From the Series of Essays

Ritual Practices by Elaine Smollin

The vision of deities and their familiars, among animals, tends to exclude humans from those with the ability to see the progress of eternal forces in the actual world. Perhaps this is because our vision is more pragmatic. Unlike dogs and birds, we don’t feel the swelling tsunami.

Evolving from elusive confidence in a primeval world composed of real and implied danger; human vision follows along the discourse of ambiguity. Vision is led by words. Innuendo spreads rumors. However, what is spoken is not what is heard. What is heard gathers power over factual existence. What is seen in solitude then, cannot possibly disclose what is continually lost to public knowledge. And the procession of our primeval instinctive culture-of-vision becomes an experience of nature that is impossible for us to describe.

Since we’re culturally dissociated from its essence, when at last we do experience the synthesis of ecology with our minds and our vision, it is a chance to revel in our natural predisposition toward magic: the old way, the proto-historic way. Early in the last century, Dvozhenko tried it with pears in “Earth” but they were possessions, cultivated by humans, made to absorb our projections.

When nature is investigated philosophically, that is, by eye, mind, hand, stance, our retinal sensitivity to evolving climatic events, light coursing its way through a forest, for example, sets off a series of cognitive possibilities that can’t be re-invented in an image. The presencing of matter, as the phenomenologists told us, occurs when we’ve seen the substance of color and light, and our physicality altogether. When this happens, the human animal sees in another vocabulary.

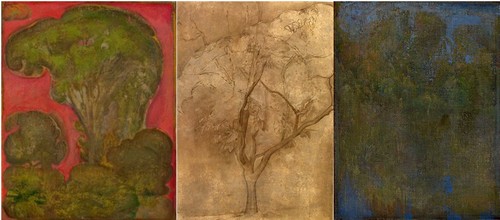

Somehow Eric Holzman extends an experience in the world into the confines of a studio, where he probably has no confines. This essay is not about his tools including a wonderful, lively, art historical knowledge, because the paintings elude consciousness apprehension. The moment you see them, they dart away from your grasp to their right place in the eye of the unconscious, that is much more at home in the forest, that place none of us moderns live in, culturally speaking. So here a tree is emblematic of something lived, but not an artifact-motif.

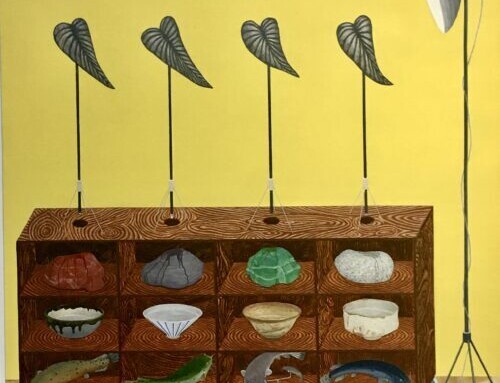

His visual experience of the wild and existence extends itself even to a pot of blossoms to retain its mortal place in the divination of appearances in Eric’s world. As soon as I begin to be comfortable with his abilities by associating them with, say, Redon’s, Road to Peyrelebade, an historical analogy to western painting fails.

In the Redon, the pulse of those chimera of the forest glade are attached to an experienced (or more likely remembered) moment of real activities among light, form and space. I’m also not convinced that making an analogy between any living painter’s work to others from another cultural point in time works, since the market creates comparative order by the very nature of being a marketplace, and, we don’t experience the world as they did.

Now, since the inception of modernism, we’re as distant from experience of actuality as we have ever been. Neither are we in possession of an integral synthesis of human perception and divination, the substance of daily life in the past. So how does a material formulation on the edge of that experience evolve in Holzman’s studio?

I placed the image of Samvara and Vajravarhi here because Yidam deities, Samvara included, have no physical form, but are composed in the visions of people in possession of amalgams of symbolic elements. If there are any symbolic elements in Holzman’s work they’re a totality- made as if he specializes in showing the whole “amalgam” in one sweep of the brush. However the row is long to hoe. The nature of his re-imagining is not of a scene but of a context of feeling. The paintings, drawn with brush over a few years, reveal a persistence to elude discernible judgments about form so he can obfuscate it and reveal its sensate presence.

Form is everything one might say. As if, at home in the studio he knows he can try to answer a significant need of the sixties’ and seventies’ generation: to find the spirit to see through the commodification of everything. An adept at the spirit of the times, Holzman was a professional rock percussionist before he was a painter.

Yet, back to Smavara, I placed him here to allude to attributes of Holzman’s worldview. Unusual as his family lineage might have been, it grows more typical as the world’s cultures collide with a new familiarity today. Still, it’s not everyday one finds a New York City painter whose great grandfather was the Jewish Chief of Police in the extremely cosmopolitan Turkish city of Izmir, ancient Symrna. It’s not the ethnicity of religious culture I refer to here since back in Izmir, trans-regional culture could be more fluid then, and, was certainly understood differently then than it is now. Rather, Samavara is here to represent how trans-regional European mentalities of the past, allowed, instinctively or by tradition, for the presence of a patron deity, or ancestral motives, in their lives.

What our ancestors knew of spiritualized being and behaviors shaped by beliefs, were a part of explicitly violent worlds, subject to sumptuary laws and life-locked professions. But ultimately, even ideas, if not only violence, would free them. Within the expiration of two to three generations we trip, ideologically unfettered through life, making up the synthesis of belief and pragmatism as we wish. In our present period of such freedoms, (as Schopenhauer would say), you can’t separate the perceiver from the perception in Holzman’s studio.

Eric Holzman’s works are on view at Lori Bookstein Gallery, in New York City.

Captions All Eric Holzman images courtesy of the artist.

1. Elm 2008-2014 oil canvas 20 x 16”

2. Tree in Yonkers II, 2002, watercolor and egg tempera on prepared paper, 13 x 9.5 inches

3. Afternoon 2014 oil on canvas 12 x 9 inches

4. Late Afternoon/Crestwood II, 2013-1014, oil on canvas, 10 x 10 inches

5. Sleepy Hollow III 2009-14 oil on canvas 14 x 2 inches

6. Kesico, 2000, oil canvas, 12 x 9 inches

7. Terracotta and Roses II, watercolor on paper, 11 x 8.5 inches

8. Olidon Redon, undated, The Road to Peyrelebade, oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay

9. Tree and Car, 2014, oil on canvas, 12 x 9 inches

10. Forest at Crestwood, 2009-2014, oil on canvas, 10 x 8 ¼ inches

11. Samvara and Vajravarhi, 12th c. stone, Tibet

* Cover image: Eric Holzman – Sleepy Hollow II 2014

Oil on canvas 18″ x 14″