by Jairo Dueñas

The hands of a philosopher trying to capture time frozen in an old family photograph can turn it into an excavation site. This is the work of the Colombian artist Andres Vergara. Portraits of memory and oblivion.

Anyone hammering on a large photograph against a wall is without a shred of doubt a lunatic that should be handcuffed. However, if we become his accomplice, driven by the curiosity of how such madness unfolds, there can only be two epilogues: first, we would end up at the police station for being bad citizens, and second, a more sumptuous and exquisite one, we would become the privileged witnesses of an act of pure creation. Andres Vergara did this in 2017 when he began to carve an old photograph of a couple dancing in a party; as he sculpted it against the wall, the wall became part of the image, thus carrying a second memory in homage to the one already vanishing.

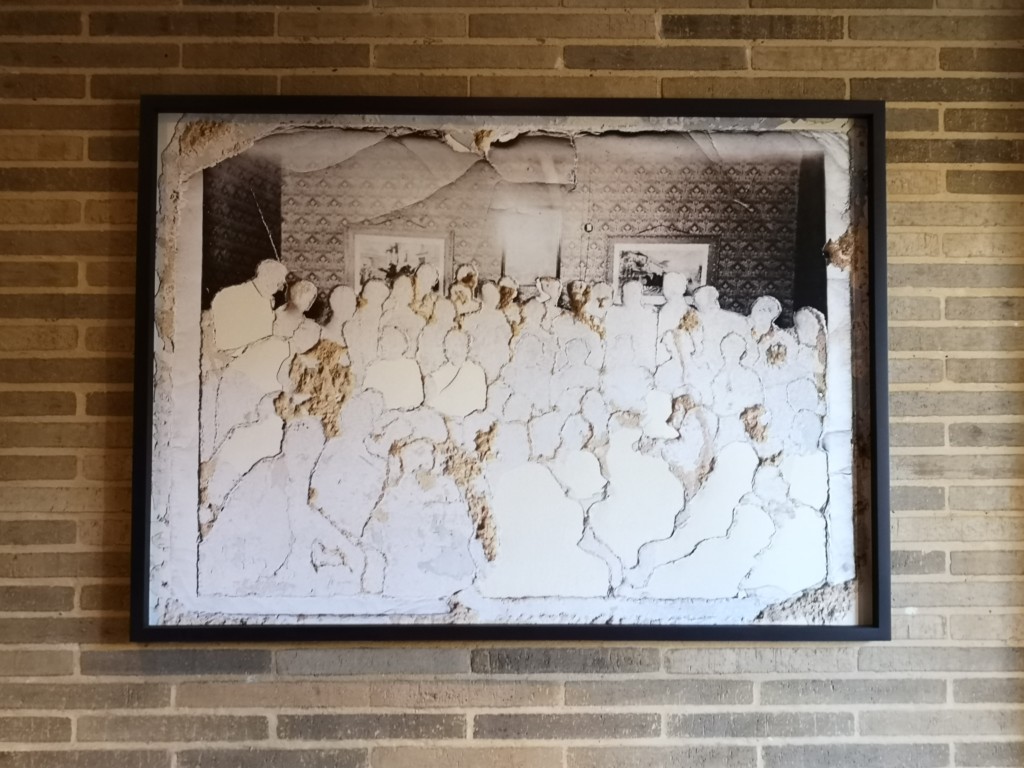

He made a second attempt to “sculpt” another photo on the studio wall, this time (showing) it was the photo of a group of people in ochre celebrating in an old hall. It is, of course, strange to see someone carving an image in paper, sensitive to light, against a cement wall in a room, and yet this was what he wanted to do.

With each pounding of the artist’s small hammer, the details of people’s features began to blur. Their gestures and gazes began to erode as though they were ghosts, while something began to gain expression, to grow and tinge, to fortify despite the wound wedged by the metal, something began to seethe from a whisper into a discourse over the passage of time.

His work, completely impulsive, at last responded to his disquietude: how to be a photographer without using a camera? He now had the answer: to turn the processed photograph into his work material, just as the stone is to the sculptor or the canvas, to the painter. However, something happened to this archeological intervention on the ancient photo: instead of negating an image, the memory of what was eliminated never actually left.

“In my art”, said Andres unapologetically, “there is always this gesture of paradox to remove, to discover, to bring something to light. My work as an artist is a labor to explore reality by means of the materiality of photography.” In order to rediscover the artist in him working in such a light sensitive field, the philosopher of Colombia’s Los Andes University had to first overcome the anxiety of working with hands.

He was not manually skillful, and his preliminary vision of art as a world full of talented people capable of finding perfection in their work, excluded him; he was an outsider. The desire to study a foreign language drove him to London as an apprentice, but the greatest lesson he got was to see with wonder, as an astonished observer, when he worked for an art moving company.

The opportunity to see, for example, the treasure trove of the largest African art collector that filled a five-floor mansion near Hyde Park, or moving artwork for the Saatchi Gallery, one by one, to its new address in Chelsea, showed him that art was something else. “I had no idea”, confessed Andres, “that art could be all that”. A world of wood carvings, Damien Hirst’s shark, or the hollow face of an artist molded in his own blood, convinced him that art was more than the glitter of perfect architecture, that it could also be the stigma of a body wounded by light and time.

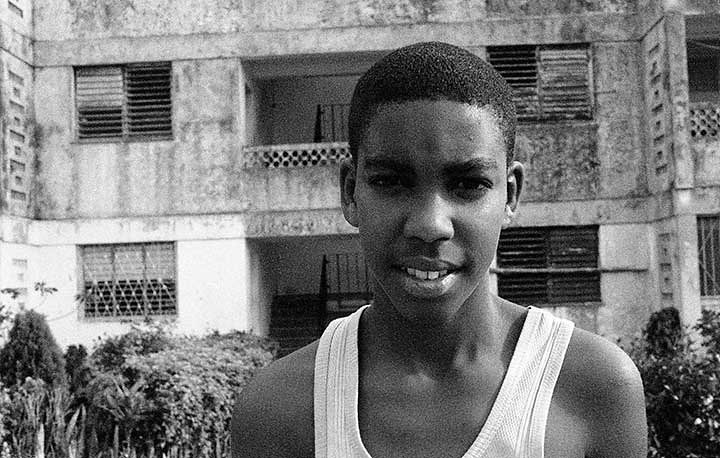

Andres returned to Colombia determined to explore photography, which took him to another journey, this time to Cuba, to a film and photography school in San Antonio de los Baños. There he took his first portraits of children and adults, peasants of corn and tobacco farms that lived in an old factory that after the revolution became their home.

Upon his return from Cuba, he started to create his first compositions through the visor of his camera during a trip to Ecuador, Peru, and southern Bolivia. It was a direct confrontation with landscape. He discovered how to compose the reality around him through the lens of a traveler. His work was published in a book titled “Ventanas del silencio” (Window of Silence).

Intimate Spaces

His work with landscapes led to his first exhibition in Colombia in 2013 titled “Relatos invisibles” (Invisible Stories). It was an installation of photographs in light boxes, showing mysterious places of his childhood, accompanied by sounds of nature, giving one the feeling of witnessing a fraction of time in that environment.

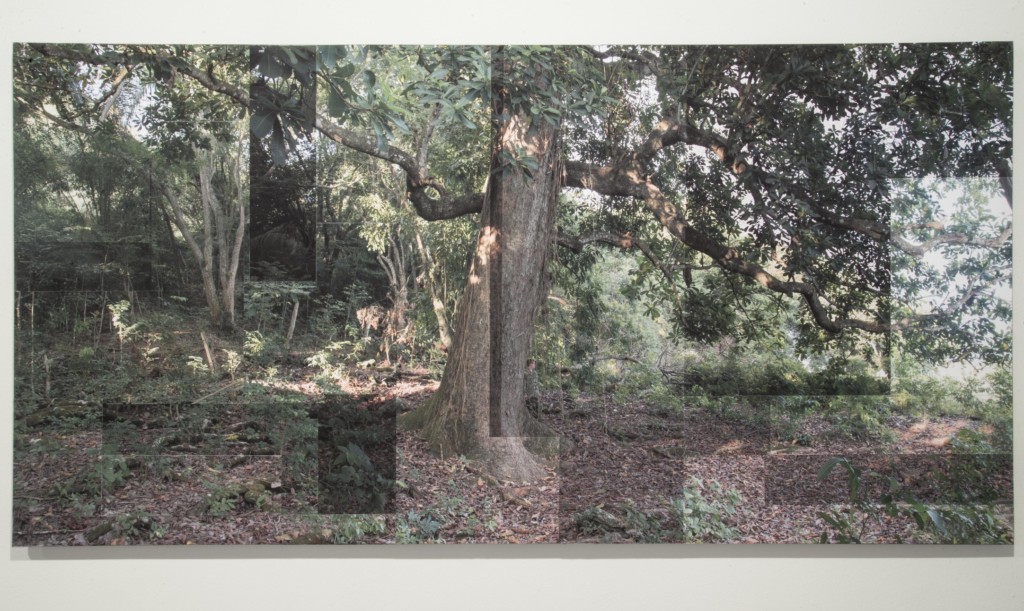

One year later, he showed “Paisaje con soldados” (Landscape with soldiers), a photo of a superimposed images of a landscape with a huge tree, each layer with changes of light, time and characters.

“This work”, Andres explains, “speaks out the fear that breathed in the landscape of my country, and whispers that the guerrillas and paramilitary were there. The war was there although you couldn’t see it clearly, like the characters the work on in the old Caracoli over 200 years ago in my grandfather’s ranch”.

In that same ranch the artist committed himself to a dense project for two years. He set his camera on a tripod in the middle of the night, with the diaphragm wide open, and used a flashlight to draw different familiar spots of his childhood, as though he were digging something out of those empty landscapes.

In 2008, following his mother’s death, the artist received a box of photographs from his father, who had settled down in a new relationship and built a new family. Looking at the heap of photos, he began to feel that all and every single photograph had already been taken.

“I had the certainty”, he sentenced, “ that the entire world was already photographed. All photos are taken, all of them, the valuable and the worthless. All photos are right there”. He then stopped taking pictures and began to work with a universe of existing photographs found in flea markets and his family albums.

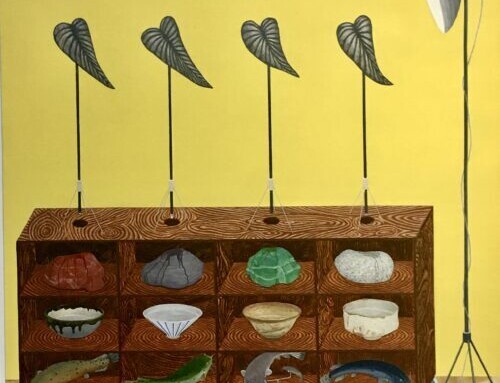

He started to experiment in his studio with 15 photos of landscape, by first digitally mutilating them into fragments, so that in some instances, he removed the mountain and only stayed with the sky. As he placed one of these fragments on the wall, he accidentally locked the photo material onto a new surface of stone and the image began to transform into a sea of signs that hinted a collective imagery. This series of stone blocs titled “Peso muerto” or “Dead Weight” was exhibited at the Sala de Arte Sura gallery in Medellin, Colombia.

Today, at 34, the artist does not stop questioning why he makes art, and what art is for in his life. Sometimes he feels that what he extracts with his work is not natural water, which is essential to life, but rather a parody of water, more decanted, more spiritual, yes, but not entirely necessary. That is the paradox…imaginary water. This is how useless and yet indispensable art is.