From the series of essays

Ritual Practices by Elaine Smollin

On the road from Frankfurt-am-Main to Leipzig, departing Hessen into Thuringia, a vast heap of salt towers above the passerby. This inert, looming, giant byproduct of industry dwarfs the relevance of anything nearby. The power of its sheer enormity stuns the senses, pressing the improbability that we can stack anything of such scale so high. My companions relieved my amazement by saying, “Likewise, the women of Berlin made order of the ruins.”

Neo Rauch’s recent show at Zwirner Gallery marks a time in which the perennial act of composing images is challenged by a vast scale of reference to visual culture. And so, as if to answer a dream of New York and Leipzig cultures, I had the wonderful luck, as I turned to view a wall of expansive Rauch paintings, to see David Salle, a progenitor of complex riddles, arrive to greet and congratulate him at his opening reception. In 2014, Rauch completed imagery for the exhibition At the Well, while earlier in 2013-2014, Salle showed Tapestries, Battles, Allegories at Lever House.

We live in a moment when the outcome of aesthetic currents that were struggled over and crafted by mind into new forms of expression throughout the twentieth century, appear as freely realized approaches to form- and sequential narrative is not suppressed. Rauch and Salle, above all, consider the picture plane to be their circus of fate. To each of them comes naturally a means to assess how the long, relentless accumulation of imagery impacts us. Whether we know its meaning or not, we feel the force of this accretion, which is perhaps closer to truth.

I walked within the expansive totem-like worlds of Neo Rauch paintings at Zwirner Gallery as if to walk today, as I did in 1992, in the streets of Leipzig, Berlin, Vilnius, Riga, Tbilisi, and, Moscow, (and later on in Ulaan Bataar) in search of innocence.

On site in those cities, as in his paintings, I let the expansive dimensions of trust in appearances instruct me regarding the semiotics of past societal forms to be found in the built environment. The ambiguity of such foreign places begs our acceptance of how powerfully political processes can transfigure the material world- if any is left standing.

I left Vilnius, the pretty, humble, intimate capital in 1992 for a brief stay in Berlin. I discovered that the standing, yet, nearly ruined state of convents and seminaries in Vilnius offered comforting solace, compared with the greater spiritual and material attrition that prevailed in the east in Berlin. Vilnius the periphery offered a surprisingly more complete historical and psychic ensemble than did Berlin, the great transregional center of northern Europe.

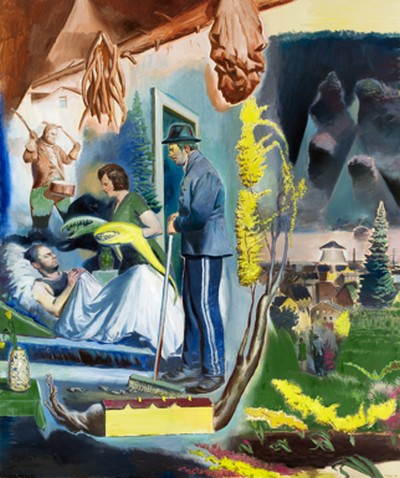

In Rauch’s paintings worlds proscribed by architecture are animated by glimpses of episodic events very much like the tense feeling of everyday life during the times of Solidarity and Glasnost. Into Rauch’s parallel versions of modernity come phantom-like people, whose culture fits securely in nature because, for them the merging of dream and reality is simply real without the likelihood that irony, revisionism or innuendo will redefine its value. It has already been redefined as the theater of past consciousness.

In Rauch’s paintings we see that essential element of nature, the co-existing ecosystem as the theater of its co-dependent metamorphosis with humanity. In peripheral societies, whose people ultimately visit the cosmopolitan world, conservative and revolutionary traditions are expected to exist side by side. Myths, stories, trauma and the persistence of hope mingle. At the intersections of Central and Eastern Europe such ambiguities are normal, embodied in the topography like familiar trains of consciousness. Ambiguity is essential as a form of psychic endurance, all the better to anticipate new tremors to economic stability and political fallout.

Neo Rauch, Das Horn, 2014, Oil on canvas

98 ½ x 188 1/8 inches

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

I’m drawn to this staging of the accretion of historical imaginings that occupy our unconscious. Anyone who lives for a time in foreign cultures relies on the companionship of visual culture in the smallest and most imposing of things- to pave the way to speech in another language.

No wonder then that many painters, whose work flows between nations and cultures, can expose this simultaneous inner, meditative trust in image-legacies. With exposure throughout our lives to the largest accretion of world imagery of all time, composition becomes a game of reason and dream recall.

Now, what is transpiring in such works that lay just beyond our ken, always just beyond reach of rational location within our personal histories, and our place in the long current of historical processes? Where are we in this projection of collective fate- imposed on us physically and emotionally? The paintings of Rauch and Salle are a great place to look.

For Neo Rauch, formidable construction of pictorial space gives us a view of psychic appraisal of sixty years of a society’s experience within geographical destiny. For David Salle, imagery that might show defiance against consumerist culture gave form, instead, to an unspoken subjugation to eroticism- to show how the pursuit of lust is correspondent with suppressed rage (in some) at the delayed call to the ideology of endless war.

In these artists’ works we can find simultaneous reflection upon their respective societies that so define this turn of millennium. Onto David Salle’s 2012 painting, Standoff, actual nude women press portions of their painted bodies onto a panorama of a vast “Enlightenment” era battle seem to suggest, perhaps, that if the young mothers of all men might diffuse the ideology of rank, valor and death; a rebirth of sense might stand in the place of war.

David Salle, Tapestries, Battles, Allegories, Lever House Art Collection

http://leverhouseartcollection.com/collectionsexhibitions/collection/367/dave-salle-studio

In many a Salle image, women are a metaphor for the body of history, carrying, as they do, their liberation from the burden of earlier times when the obligatory five- to twelve- and more births, trapped them in remorseless biological straights. While in Rauch imagery Europeans see dreams of their ancestral legacies reenacted within a topography of environs, in Salle we Americans can see reenacted the dream of our freedom from personal confrontation with the cold war as our contemplation of women’s bodies, and female psyche- as the topography of our best defense against repression of personal freedoms through ideology.

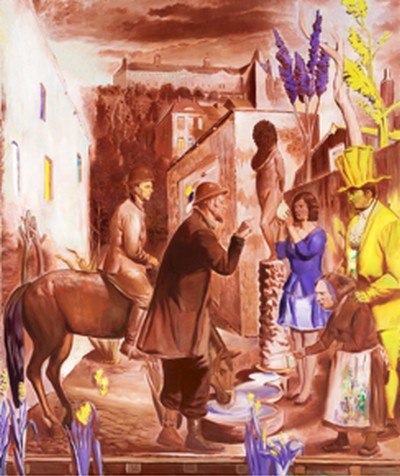

Where people living just outside of Leipzig in the former DDR saw massive strip mining for coal desecrate the landscape with reunification, today the ecological ruins are covered with new fertile farmlands and the “Neuseeland” a new “lake” district, that flooded former coal mines. Rauch seems to recall this in the 2008, Alte Verbindungen.

Neo Rauch, 2008, Alte Verbindungen, Oil on canvas 98 3/8 x 118 1/8

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Meanwhile, in Salle’s The Mennonite Button Problem of 2010 (the image appears on his website) we can see how below a tranquil sea devoid of any notion of doubt, that haunts the European imagination, solitary women replace the male warrior of ancient art as the subject of a figural frieze. In their seemingly nocturnal or subterranean lair, privacy reigns, with no sign of partner or loving voyeur. To solicit that empathy, the effort is in the viewer’s experience. This is the kind of space where Odysseus went among the shades in search of his mother.

“Molodezhny”coal mine. Mid-twentieth century deportation site.

Karaganda region Kazakhstan. Photograph by Vadim Makhorov

It’s interesting to see the title of the image of women in this substrata refer to Mennonites since it was at what would become the Karaganda coal mines where ethnic Volga Germans, Mennonites included, were deported by Soviets in the mid-twentieth century to begin to construct, at first by hand, the vast strip mines that served as the topography of their mass annihilation.

Somehow no matter how detached from actual experience the random collection of imagery may be, it is normally never irrelevant to the world into which we are born and evolve.

Which brings me to the use of buildings as a formational element in Rauch’s paintings of Gründerzeitstil. Each epoch has its formational moment. As a society’s hopes coalesce into concrete ideological form, architecture is called upon to carry the weight. The term relates directly to the late nineteenth century phase of building in Leipzig and other German cities and towns that proceeded until 1914. This movement’s style was also parodied in the term for the fault lines of capitalism and economic collapse known as the Gründerzkrack.

So to see Neo Rauch’s paintings at Zwirner Gallery in New York, is to be reminded how the opulent, even corpulent, Baroque facades of Leipzig stand in contrast to the simple geometric stucco buildings so common in the Baltic, Poland, and all of Mitteleuropa that stand, some from the 16th century onwards, as the humble partners of simple commerce among dozens of regional cultures.

In the same week as Rauch’s show opened, the anniversary of liberation from the DDR was marked by release of Jenny Erpenbeck’s new novel The End of Time. In it, the merging of past and present is a precedent for the meaning of everyday life. For Erpenbeck, a novelist and opera director, these precedents include realities of existence known to those who precede us, whose consciousness imbeds with anachronism to form a type of mental ecology. There, feelings and events left unresolved, are allowed to evolve in an unimpeded state, to flow on in the historical continuum, directly into our present consciousness.

In other words, knowing is layered and it is streaming. And what we know of the built environment, the land and our generational succession into it, is a field of experience open to the great, silent, human drama of inheritance, psychic, social, political and artistic.

This simultaneity of experience has led to evolution of painting as a repository for the unscripted visual history of the last century. Its artefactual evidence has been coded as collective pressure on individual artist’s psyche; and offered as the output of unselfconscious mastery over what we have really inherited- trial and error attempts at world peace, amidst the long age of capitalism and its antagonists.

In David Salle’s 2007, Last Night, (see his website) placed in frontal space, before the mother ships, canton ware, the body of water and a multi-chamber manor house, a woman gazes beyond her fate as if reluctant to see in it any need for change. She is placid and in no need of defenses. Another woman, analogous to a desirable mooring dock, is in self-possession of the prime of her life, muscled and agile as the reptile, dragon or snake, on the Canton plate.

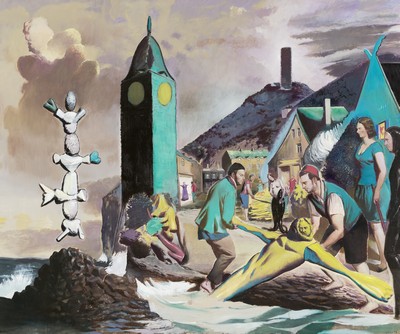

Neo Rauch, Marina, 2014, Oil on canvas. 98 ½ x 118 1/8 x 2 ½” (250 x 300 cm)

Courtesy David Zwirner New York/London

Neo Rauch’s, Marina, 2014, cuts a cross section through the past. The propeller-armed crucifix (whose stylized arms are consistent with early Gothic crucifixion figures) is breached from the ocean, into the arms of the locals between two monolithic towers. The foregrounded building is a commonly seen modern era steeple of Lutheran churches, the other, is a medieval fortress tower. This juxtaposition of built environments isn’t as inscrutable as some American reviewers would have it. Rather, these are common symbols of European civilization at the end of the migration period, Volkswanderung, and the Reformation that embodies most towns in Central and Eastern Europe- and even some industrial cities in New England in their own period of Gründerzeitstil, that reveal the fabric of our early technological society.

In Boing Boing, 2007, Salle repurposed an image of the “ideal worker” with a totem, a meal, and, a vortex within which people spin by. At the opposite end of this spectrum, a pot of captive flora is perched above the female worker’s head. The ancient art of carrying it on her head is lost to the technologies that fail to affect her style of dress- that reverts back to life on the prairies. In 2013, he created an iconic image for the new demographics of our post European-American society, in which an Asian woman directs her glance beyond an Aleutian totem.

Image making involves attempts to resolve ideological fixations to ask, Whose reality is this? How do we assess the psychic leverage that the authors of ideologies try to assert on us?

Salle and Rauch approach this intricate process from within its fulcrum, tilting our frame of reference from societal pressure to the inner freedom of individuals, who each in their own way must undo ideology and do the tough work of reading deeply into these alternative cultures of reason.

These painters grasp a type of psycholinguistics that evolves in such a parallel historical record.

The coded color Rauch imparts in the pink and turquoise on sepia, Der Felsenwirt, for example, suggests a select cognitive filter, through which a painting can embellish or invade a plane for reckoning with the unfamiliar stages of personal, and, universal histories- and through this scheme, even the subconscious must somehow pass.

Psyche strives to preserve her vibrant being, aided to various degrees by the unconscious to seek balance among so many parallel worlds. Rauch’s paintings always suggest a reckoning with both belief and disbelief and never fail to examine how we may parse a psychosymbolic thread of images. His paintings provide us with a link to social-cultural innovations of the earlier century that were left incomplete.

*Cover image: Neo Rauch, 2007, Die Fuge, oil on canvas, 118 1/8 x 165 2/5 inches.

Courtesy David Zwiner, New York/London