From the Series of Essays

Ritual Practices by Elaine Smollin

In Mamma Andersson paintings, what is apparent is always the flip side of consciousness.

The present may as well be the past, while the past with its heavy hand, can deftly reveal a sudden lightness of being. From where comes this painter’s dialectics?

An Andersson painting is never about what is merely on its surface. She proposes stunning demands for an audience. Precisely at the moment when non-objective painting flourishes in New York with lush, flowing material presence, making surface appearances so attractive; she fills two enormous Zwirner galleries with semiotic secrets that defy trust in appearances.

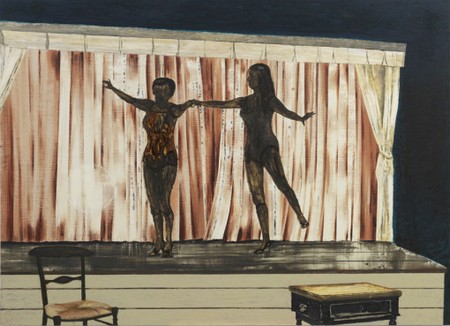

The theme of Behind the Curtain may well have been “This is not a pipe”. And, if it isn’t as Magritte proposed, what then? Andersson designs a serpentine journey toward a destination for meanings and the route is replete with secret passages.

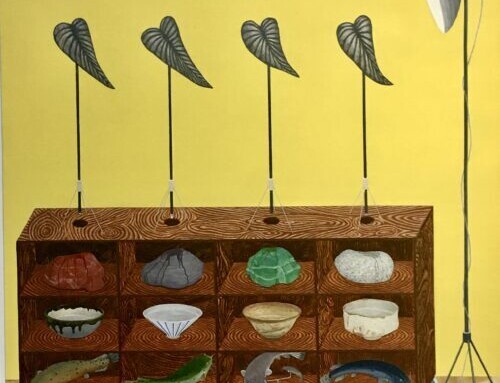

Every feature in an Andersson image is endowed with an independent life force, coded, it seems into the fabric of her imagery, to prove its independent nature. Panoramas of Nordic lands are so vast they might defy human presence, but always include the existential reality of people. Likewise, in her austere pictorial designs of intimate space in modern interiors, the apparent vacuum of meaning presses its value.

Mamma Andersson and Ossian Rossland Lindvall working on murals for her

2015 solo exhibition Behind the Curtain at David Zwirner, New York

Photo by Scott Rudd.

Behind the Curtain places all the responsibility on us to discover the status of our powers as viewers- but not only, she makes us the object of her revelry on the threshold of response and spectatorship.

Among the paintings we look into the semiotic rhymes between a distant Nordic past and their sudden appearance in New York City. A walk down the street to the giant cut-outs removes us from the elusive meanings of nostalgic objects. Once within the theater-like set, the “little people” of the paintings sudden dwarf us with their alternate form, gigantism. Nevertheless they remain cryptic to us, reversing the quizzical gaze we placed on them.

This situation seems designed to predict how precariously our visual response is bound to mutual intelligibility. The immense cut-outs stand literally behind a curtain. Distant from us, they show off the liminal space between living in the moment and a sense of mortality suspended in a fictionalized past; reminding us how at home Europeans can be among existential dilemmas of this kind. And the new pandemic phenomena we contemplate, how will we all know each other in these global times?

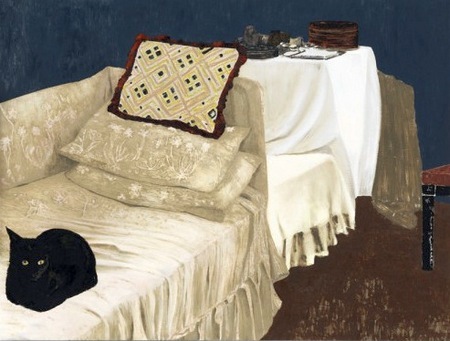

The contradictions in Andersson’s show are carefully calculated. Knowing the relevance of things, she shows us, has its joys and its limits. She enlisted her paintings to show how styles of knowing can belong exclusively to the past. And myths of origin, once common to European women, in particular, as embodied in her choice of artifacts, refrain from any revelation of their original meaning to the women of their time. Here the tablecloth I mentioned in the earlier Soutine essay, has defied the Diaspora. However the women’s faces are vacant, blackened, resolutely towards an era unknown to us, the time of forgetting.

The intentional absurdity of these curious paintings work like a psychic trap that Ingmar Bergman would devise. These are really a kind of tricky mental assemblage in which her sly use of innocuous antiques is used to locate our consciousness among historical artifacts, the kind we can’t quite attach a meaning to.

The meaning is our mutual un-intelligibility. A serous yet playful lack of fidelity to origins emerges. This serious play reminds me of East European jokes, so tragic as to shock a westerner but hilarious enough within the culture, since dark humors allow us all a role in fates that turn up as always, eternally beyond our control.

Left: Ingmar Bergman, Still from Seventh Seal, 1958

Middle: Mamma Andersson, Hangman, 2014 Oil on panel 49 1/4 x 49 1/4 x 3/4 inches

Right: Ingmar Bergman, Still from Seventh Seal, 1958

Perched on his fresco scaffolding, the painter is in the midst of his work- to show the distancing of people from factors of time. With the grim reaper in town, during the on-going Crusades, the late medieval Swedish painter may well take up the narrative, let’s everyone reckon with the trajectory of fate. As I believe Andersson has done, and, in the process tests our identities with a grave power, that remains nevertheless, like Bergman’s- full of mirth.

Left: Crib, 2014 Oil on panel 41 x 48 1/8 x 1/2 inches

Middle: Mimicry, 2014 Oil on panel 49 1/4 x 39 3/8 x 7/8 inches

Right: The Uninvited, 2014 Oil on panel 43 5/8 x 65 5/8 x 3/8 inches

She conjures up a distinctively Swedish mannerism to join melancholy to mirth, paving the way through a view of modernity, bringing keen historical imagination into play with vernacular drawing and painting traditions. Andersson’s use of Trompe-l’oeil is a metaphor for how our minds defy an image of women’s former place in society that is more remote by the second from our experience today. As above, the female figures vanish within their forms, beamed up to the past.

This architecture of consciousness relates a narrative motive in the painter’s touch to a graphic logic. In the age of Photoshop as an image-shop, she summons up a highly factual description of what is normally a non-verbal awareness, to describe forthrightly (however cryptically delivered) – how we live within a fictional façade: the material culture of others’ existence.

She exposes us to a new symptom of our society: our simultaneous knowing of a specific national past and each viewer’s late modern post-national, post-ethnic present. She is allowing us to peer through a veneer of modernity that is out of focus, suddenly so, as if obliged to fuse now to then. Andersson leaves us on this threshold, to puzzle out how we embrace this discontinuity.

The scaffold, a corset, the theater stage, they are a time machine with a high wire act enabled by explicitly depicted antiques and a staged dance between two women, that speaks for me of the long extinct existence of Nordic matrilineal societies. Retreating from the Mid-Summer’s Night fertility rites they dance together in the dark. Hopefully it is merely deep winter and they’ll return to the light.

Her accumulation of associations and unstated meaning suggests that Andresson sees the past with an immediate need to crack open its contents. In doing so she refers to the silent status of material and matter. The moment an artist employs veneer, as in the Baltic Biedermeier secretary, or, lace for that matter, there is an implied reference to refinement of raw materials and handcraft- to the primary matter and ingenuity of the studio. This timeless process brings us a bit closer to our historical continuum and the origins of modernity- an era that is fortunately for us, elusive in its end point.

A short time ago, let’s say in the lifetime of Basquiat, 1960-1988, painters, him in particular, retooled the early twentieth century forcefulness of primitivism as a medium. Sets of freshly conceived Gestalt images created a scale of new references. These ideograms and totemic images, coursing their way through the painter’s cultural status evolved into a new means to re-qualify the purpose of painting as a frank iconography of psyche.

How fascinating it is to see a Swede do this in 2015. Mamma Andersson’s recent show at Zwirner Gallery presses the point of what we in New York City may still recognize, if not identify, as currency with material artifacts in the European psyche.

Long ago, the original Nordic fresco painters stood aloft on the scaffold of a country church.

(Ingmar Bergman, Seventh Seal, “What are you painting” Scene: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CPs1yuBW8u4)

The Crusades that aligned the Christian, Pagan, and, Muslim faiths as adversaries, were playing out elsewhere. The long mutual harassment and its outcome shook local consciousness as the witnesses to events filtered back home to domestic life. Andersson’s acrobat hangs from the high-wire, faces his shadow between black urns- as the shadow rises over and beyond him and the black cat looks into infinity.

*Image on slider: Mamma Andersson – Heimat Land 2004 31.5 x 110 inches

*All Karin Mamma Andersson images are provided Courtesy of David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London