By Light-man

You have probably heard of James Turrell’s impressive solo exhibition currently on view at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. I was informed that this was the second most popular exhibition ever held at the museum, the first being a Picasso show.

Some people might have told you they were dazzled by the main site specific installation called Aten Reign (2013) on the first floor. Others might tell you that they had to stand on long lines to see an installation inside a dark room on the top floor called Iltar (1976), and when they finally entered the room, all they found was a mysteriously quiet space, where nothing happened. No matter what they say, all commentaries are inevitably addressed to the issue of perception.

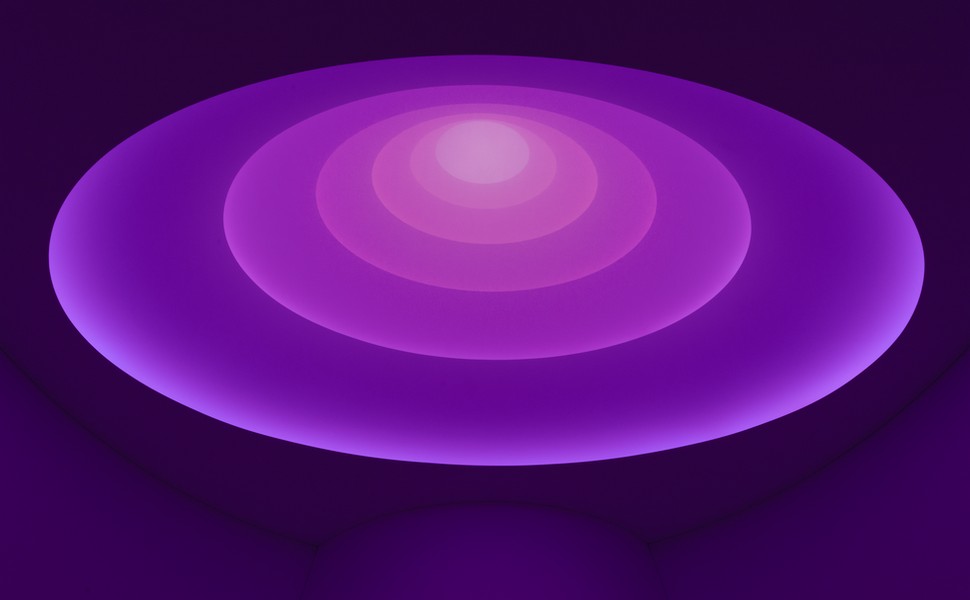

James Turrell

Aten Reign, 2013

Daylight and LED light, dimensions variable

Installation view: James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

To me there is no way to describe what the exhibition is about. I bet you no one has succeeded either.

Museum catalogs can give you a general idea of what these installations look like, but in this experience of James Turrell’s work, you’d realize that what you see may not be what they really are.

One such work of art can only be experienced. So, I can only tell you what I personally perceived and felt.

As you enter the museum, the first thing you’d notice is the Aten Reign, that has spectacularly transformed the entire rotunda of the museum into a space set for the viewers to look up at the opening on the top roof, where light does not pour in but is sustained by the interplay of a series of interconnected rings lined with LED (light-emitting diode) fixtures, forming five concentric ellipses that reflect the pattern of the museum’s helical architecture, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

You’d encounter an interesting spectacle, almost archaic and ritualistic- a multitude of dark silhouettes of people gazing upwards, either seated or lying comfortably on a large round mattress in the middle of the room, or just standing, bathed in lights of intense blues, pinks, or oranges, reds, in subtle and slow changes of different tonalities, as if they were awed by something magnificent descending upon them.

As I lay down with the others – men, women, children, young, old, from all over the world- on the mattress, I also joined then and looked up. A woman did not stop talking to her companion; her jittering disrupted my experience, so I plugged my earphones into my I-Pod and accidentally hit a meditative song called Emerge, by the American composer Adam King.

To the binaural tunes and beats of Emerge, at one point I thought I was seeing the center in the middle of the rings growing, and the light expanding, and suddenly the light became more important that my perception of self. It was eerie, but I felt a sense of belonging as never before, as though all the people around me, lying on the mattress, were glued together and we became one single body, although I was clearly aware that we each had a separate body.

Somehow we all shared the same light, and yet the light was never the same. It was changing all the time, and sometimes it went back to the first light that I had seen, as in a timed cycle.

“I like that”, one man could not help but gasp, when the light became monochromatic, showing different tonalities of greys and whites.

It took one hour to see the full course of light transformation, and yet, no one seemed to want to leave. You could stay there the whole day, thinking about your life and different passages of your life, feeling at last the beauty of something you have forgotten.

At one point tears filled my eyes, and I am not the kind of person easily to shed tears. At the same time, I realized that I was also smiling.

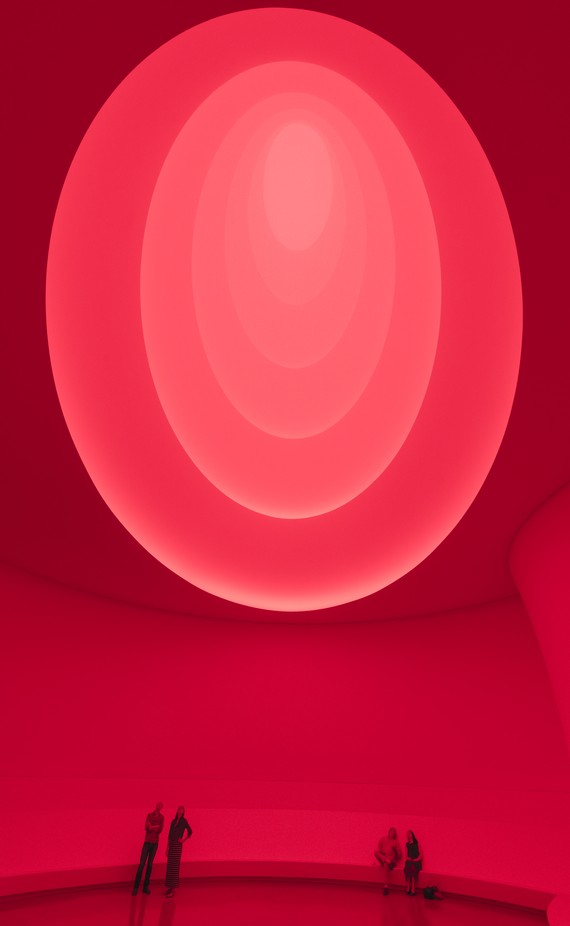

James Turrell

Aten Reign, 2013

Daylight and LED light, dimensions variable

Installation view: James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

The people by my two sides did not stir. The chatty woman was no longer talking. The room was full of the noise of people walking in and out, and yet in the midst of the sounds of around 100 people, and the music, there was a concrete silence that stubbornly remained.

As I ended my 60 minutes, I stood up from the mattress and looked down at the people around me. I thought I had been the only person who had smiled, but no, everybody was smiling.

I did not begin the exhibition with the Aten Reign, in fact, it was the last one. I started from the fifth floor, where I began this journey seeing an installation of utmost simplicity of space and light.

To see this project, sometimes you needed to be on a long line and wait from 30 to 45 minutes.

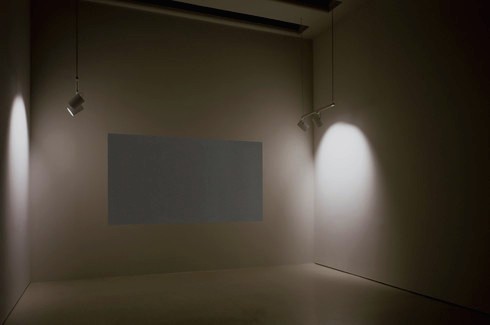

One viewer complained, “You have waited and waited, expecting to see something, but when you finally got there, all you saw is nothing”.

The visitor was right; at first glance there was nothing special in the room. All you saw was a dark room with a large grey plane in front of you and two lights strategically placed from the upper parts of both right and left walls. But, if you stayed a little longer, and looked again at the grey plane in front of you, you’d realize that it was not a solid surface and it was actually hollow, and it was the lights by the two sides that gave you the sensation of the solid plane, and then it would dawn on you that not everything you saw was what it was.

In that particular moment of realization, I felt as if I were in some elevated plane of consciousness, where everything around me was synthesized into an instant of sublime existence. I guess I was not the only one, as some people actually sat down on the floor cross legged, and meditated.

James Turrell

Aten Reign, 2013

Daylight and LED light, dimensions variable

© James Turrell

Installation view: James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New

York, June 21–September 25, 2013

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

According to the museum, In 1976 Turrell designed Iltar as one of earliest examples of the works he calls Space Division Constructions, which are basically installations featuring a bifurcated room; visitors peer into a “sensing space” through a large opening in the partition wall.

This aperture bears a knife-sharp edge, and the light fixtures that flank it create blushes of electrical light in the viewing space.

Turrell has compared the effect of these lights on the viewer to that of standing on a theatrical stage: Under spotlights the audience disappears into an inky void, but outside the light a performer can see again.

“In the Space Division Constructions, this state of partial blindness contributes to the impression that the opening is actually a solid plane of color on the wall.”

All of Turrell’s works in this exhibition not only explore possible manifestations of light and space, but also invite us to look at things in a different way.

The glowing cube apparently floating in the corner of a room in Afrum 1 (White) (1967) turns out to be not a solid object, but the effect of light installation.

Iltar, 1976. Tungsten light, dimensions variable. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Panza Collection, Gift, 1991, 91.4077. © James Turrell. Installation view:James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, June 21–September 25, 2013. Photo: Florian Holzherr

In the Annex Level galleries, etchings in a series called First Light (1989-1990) explores how the aquatint technique can invoke qualities of radiance.

The apparently bright gap towards another space in Prado White (1967) is actually light projected on a solid wall.

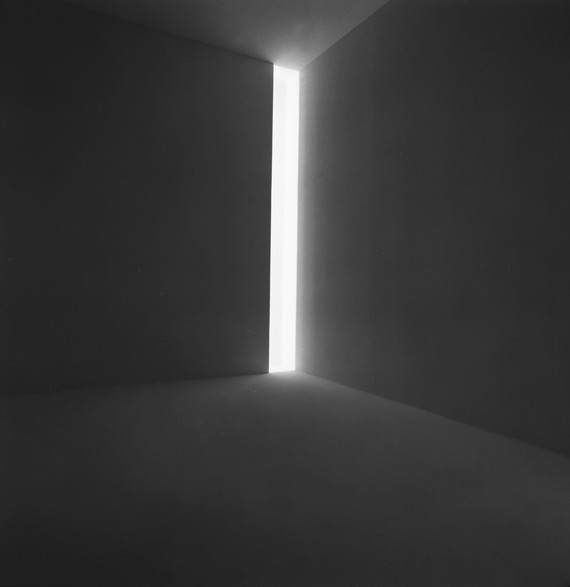

Along strip of fluorescent light solemnly pours out from behind the wall in Ronin (1968), gives the sensation that the light came down from above the ceiling.

James Turrell

Ronin, 1968

Fluorescent light, dimensions variable

Collection of the artist

© James Turrell

Installation view: Jim Turrell, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, April 9–May

23, 1976

Photo: Courtesy the Stedelijk Museum

I was glad that I’d started my experience with simplicity and ended with the longest and most intense and complex experience of Aten Reign.

When I walked out of the museum I looked up at the sky. The rain had stopped and the sky was cloudy. I looked at the shapes of the clouds and remembered the Aten Reign’s center, where shapes of real clouds could be seen behind the glow of natural and artificial light. And it stayed on in my mind.

I knew then that I could be certain about one thing, that when I looked up at the sky again, I would never see it in the same light again.

If you’d like to know more more about James Turell and his work, CLICK HERE.

*Photo on slider:

James Turrell

Aten Reign, 2013

Daylight and LED light, dimensions variable

© James Turrell

Installation view: James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New

York, June 21–September 25, 2013

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

*Photo on Featured cover:

James Turrell

Aten Reign, 2013

Daylight and LED light, dimensions variable

© James Turrell

Installation view: James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New

York, June 21–September 25, 2013

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

* Adam King music: