When we went to see a major solo exhibition by the contemporary artist James Turrell at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, we saw a side show on the 4th Rotunda called New Harmony, Abstraction Between the Two Wars ( 1919- 1939).

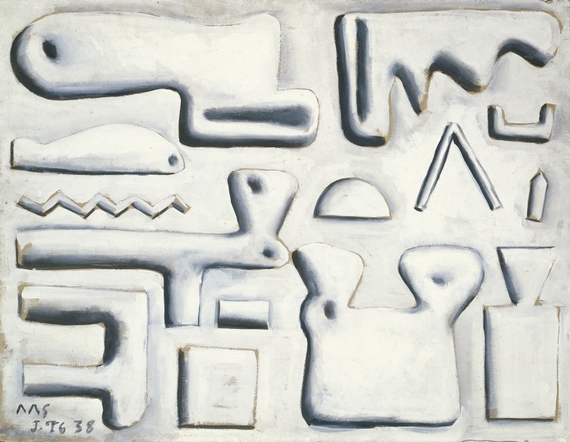

The show, named after a painting by Paul Klee in 1936, put together 40 works of 20 artists in the period, that believed in the role played by art to construct an ideal world based on harmony.

Paul Klee – New Harmony (Neue Harmonie), 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 7/8 × 26 1/8 inches (93.6 × 66.3 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 71.1960. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

It is not usual to find so many people in a side show, next to one of such impact and contemporaneity as Turrell. But, viewers filled up the exhibition room, they were interested, focused, reacted, and lingered in front of the paintings longer than expected.

We wondered why. Why does the issue of harmony matter now, in 2013, when we are no longer caught between world wars? Why the dream of a handful of artists for a utopian world should still evoke relevancy?

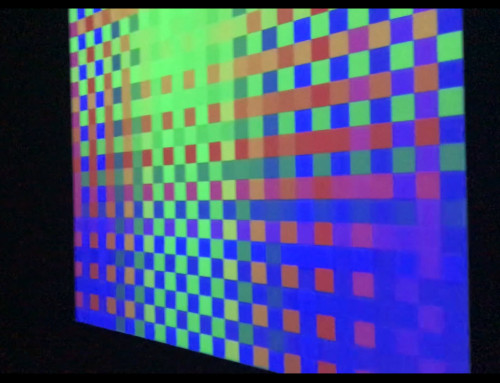

Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, Theo Doesburg, Joaquin Torres Garcia, Alexander Calder, Fernand Leger, Alberto Giacometti, Francis Picabia, Naum Gabo, Josef Albers, Vasily Kandinsky, Laslo Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters, Joan Miro, Jean Arp, Frantisek Kupka, Georges Vantongerloo, Man Ray, Jacques Villon…

The names of these artists still resonate in our memory. The movements that they created and activated changed the course of art history and in many ways the overall aesthetic perception of the time, freeing people from existing shallow and stagnated visions that had attempted to stop the natural human drive for evolution and progress.

De Stijl, Bauhaus, Surrealism, Constructivism, Dada, Merz or the collage culture… inspired whole generations to move forward in spite of destruction and despair generated by war and devastation.

![Georges Vantongerloo, - Composition Derived from the Equation y = -ax2 + bx + 18 with Green, Orange, Violet (Black) (Composition émanante de l'équation y = -ax2 + bx + 18 avec accord de vert...orangé...violet [noir]), 1930. Oil on canvas, 47 × 26 7/8 inches (119.4 × 68.2 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 51.1299. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Pro Litteris, Zurich](http://inveroart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/51.1299_ph_web.jpg)

Georges Vantongerloo, – Composition Derived from the Equation y = -ax2 + bx + 18 with Green, Orange, Violet (Black) (Composition émanante de l’équation y = -ax2 + bx + 18 avec accord de vert…orangé…violet [noir]), 1930. Oil on canvas, 47 × 26 7/8 inches (119.4 × 68.2 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 51.1299. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Pro Litteris, Zurich

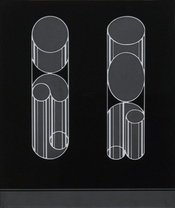

Fernand Léger – Mural Painting (Peinture murale), 1924–25. Oil on canvas, 71 × 31 5/8 inches (180.2 × 80.2 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 58.1507. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

These movements offered new ways of art expression that were directly connected to a universal language of creativity through geometry and abstraction, and explored different levels of human consciousness, psychology, visions and spirituality.

Although the exhibition title clarifies its historic significance, the dimension of the message and aspiration of this group of artists has surpassed the frontiers of time and space, and has arrived in the present century, tapping on the doors of our consciousness for a look and reflection of the same issues about life, evolution, communication, and the role played by art and creativity in the construction of our world and life style.

Are we still struggling to build our world, our environment, our life style? Do we still want to have a better life for ourselves and our children? Are we still Googling, Facebooking, Twittering, Wikiing, reading by all means, surfing everywhere, meditating, sharing information and insights, searching for an answer?

Can we really brush aside the role played by art and creativity in this quest and endeavor? Maybe the works of the artists of a “new” harmony still have much to reveal to us.

Francis Picabia – The Child Carburetor (L’Enfant carburateur), 1919. Oil, enamel, metallic paint, gold leaf, graphite, and crayon on stained plywood, 49 3/4 × 39 7/8 inches (126.3 × 101.3 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 55.1426. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Kurt Schwitters – Merzbild 5 B (Picture Red Heart-Church) (Merzbild 5 B (Bild rot Herz-Kirche)), April 26, 1919. Tempera, crayon, and paper on cardboard, 32 7/8 × 23 3/4 inches (83.5 × 60.2 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 52.1325. © 2013 Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

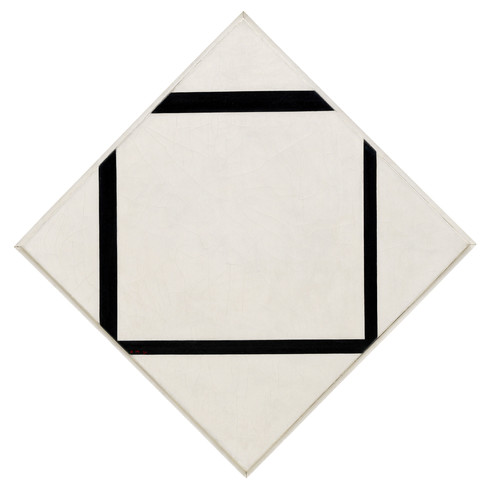

Piet Mondrian, Composition No. 1: Lozenge with Four Lines, 1930. Oil on canvas, 29 5/8 × 29 5/8 inches (75.2 × 75.2 cm); vertical axis: 41 3/8 inches (105 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, The Hilla Rebay Collection, 71.1936.R96. © 2007 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

*Photo on Slider:

Theo van Doesburg

Composition XI (Kompositie XI), 1918. Oil on canvas in artist’s frame, framed: 25 7/16 × 42 15/16 inches (64.6 × 109 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 54.1360

Photo on Cover:

Jean Hélion

b. 1904, Couterne, France; d. 1987, Paris

Composition, April–May 1934. Oil on canvas, 56 3/4 × 78 3/4 inches (144.3 × 199.8 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 61.1586. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.