Every two years art lovers all over the world pay attention to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and expect to see a most radical, shocking, daring and controversial exhibition in the United States.

Since the museum founder Gertrude Vanderbilt introduced the idea in 1932, the Whitney Biennial event has become the longest running showcase of contemporary art in the country.

In some years, the shows did shake the foundations of art making and concept. In others, they enraged viewers or simply went unnoticed and receded into obscure shadows of repetition and boredom.

This year, the curators Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley thought that the world is in a good moment for a “quietly radical” exhibition of pioneering art, but the response evoked by a few powerful pieces in the show is anything but quiet.

We have selected the following best works in the 2019 exhibition, not because they have introduced anything revolutionary in terms of art making or medium, form, aesthetics, plasticity, visual-audio and any other sensory explorations, or even art related thematic or conceptual matters.

We think they have contributed to the event’s original mission to actively challenge the status quo of our world, not just by presenting a bombastic thought provoking body of artwork, but also by using the event itself as a tool of activism to tackle social, moral, and political issues without sacrificing existing aesthetic, craft and vernacular approaches of art.

Steffani Jemison

It appears that this year there is a larger number of paintings than before, and the age of artists does not seem to be instrumental for determining whether a contemporary piece of art is considered old or new.

Another interesting aspect is that it has assumed a role of research and scholarship and offers a platform for the community of lesser-known and struggling artists to show their artistic and surviving conditions especially in New York, thus posing it as a new social issue to be taken into account.

Here is our selection among the works of 75 artists:

1) Triple-Chaser is a multi-media project presented by the collective Forensic Architecture (FA) to address specifically the issue of morality and abuse of power. The FA used an Artificial Intelligence algorithm known as a machine learning classifier to search for open source images of the Triple-Chaser, a tear gas canister manufactured by the Safariland Group. A video shows heart wrenching images of tear gas attacks and the horrors of potential physical harm on the victims in different parts of the world. As it turns out, the owner of the infamous Safariland Group is Warren B. Kanders, the vice-chair of the Board of Trustees of precisely the Whitney Museum. This provoked several protests, including a manifestation in front of Kanders’ home in Manhattan, demanding him to step down.

Founded in 2010 by the Israeli-British architect Eyal Weizman, the Forensic Architects also investigates issues of political conflicts, police violence and human rights violations with the participation of architects, artists, software developers, and filmmakers.

Other videos show right-wing extremist violence against immigrants in Germany, the Mexican government’s complicity in mass kidnappings by drug lords, and the assassination of a Kurdish human-rights lawyer and activist in Turkey.

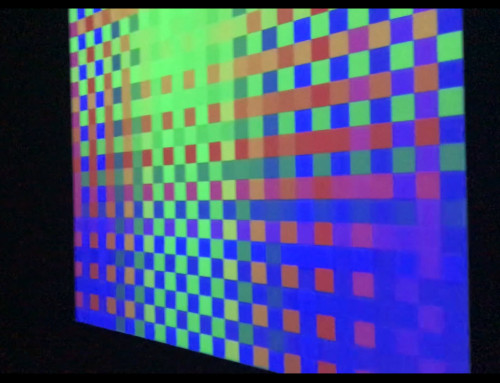

2) The Brooklyn-based Tomashi Jackson’s densely layered painting, The Woman is King (Simultaneous Contrast), 2019, presents a memorable image with refreshing clash of complementary colors and found materials such as paper bags, food wrappers, vinyl insulation strips and storefront awnings to show painful subjects that are often autobiographical. The painting is part of a series of three paintings focusing on housing displacement in New York, denouncing current development programs that transfer ownership to developers specifically targeting elderly Black and Brown property owners.

3) Simone Leigh’s sculpture of “Stick” is a compelling shape of a woman responding to what the artist considers as “outmoded notions of a female body as a vessel.” Using sensuously textured materials such as ceramic and bronze, the artist has successfully embodied an in-depth reflection on the idea of the female body in specific cultural traditions and histories.

4) Jenifer Packer’s intriguing paintings of thin washes and gestural brushstrokes are intimate depictions of friends and family merged into casual, intimate, and vulnerable domestic landscapes. They are “not figures, not bodies, but humans I am painting”, she states.

5) Kota Ezawa’s watercolor animation, National Anthem, is a monumental artistic effort to support a political protest led by San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kawpernick during the NFL games in 2016 against police violence on unarmed black people. The California based German artist, used the TV footage of the protests and painted at least 200 individual watercolors in a meticulous process to render images of kneeling or arm-in-arm football players, capturing particularly tender and moving moments of the protest.

6) Laura Ortman’s video titled “My Soul Remainer”, 2017, is a cross-disciplinary experimental work that delves into the uncanny twilight zones of music and its relationship with the music player’s environment. In this piece, she puts into practice her skills in classical music and combines it with indigenous musical traditions. She uses a four-track tape recorder, and layers a range of instruments including violins, electric guitar, Apache violin, and piano with field recordings of different environments.

7) Sculptures by the 84-year-old artist from Illinois, Diane Simpson, and her long term passion for arranging structures of clothing forms and architectural designs in different historical times into abstract interlocking planes.

8) Five paintings by the Los Angeles based artist Calvin Marcus are playful in execution and adventurous in subject matter. Dark humor and bold colors in his work appear to challenge the viewer’s perception, and yet the artist says: “The work has no tricks; it is as people see it and that’s fine”.

An excerpt of Brendan Fernandes’s sculptural installation—comprising five structures that he calls “devices,” ten hanging ropes, and a central cage—is animated at times by a group of dancers. Fernandes has likened the project to S&M culture, noting that each places “an emphasis on trust and confidence within a space where roles of mastery and submission are in play.”

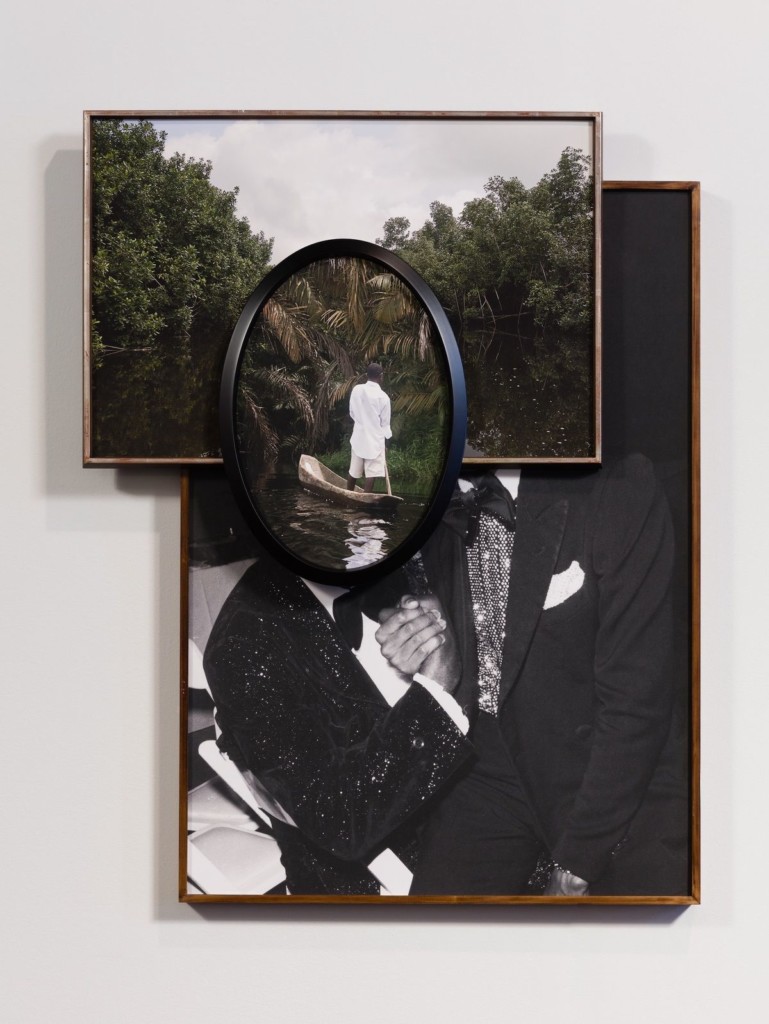

*Image on slider: Sahra Motalebi: Directory of Portrayals, 2017

Walter Price, The things that horse ourselves for uncertainty, 2018.